One seldom finds persons who really love all children. Most people show themselves selective in their affection, while some don’t like children at all. Usually it is a family affair, one loves one’s own children, but not those of other people, and this attitude gets a wide support in society, since children are implicitly considered as their parents’ property, and too much love for other people’s children is seen with suspicion.

One can often have preferences for one age range or for one gender. I can understand this, boys and girls, older and younger ones, have different minds and quite distinct charms. I am myself guilty of such bias, I prefer pre-adolescent girls. However I find it more questionable to distaste children because of their ethnicity or their lower social background.

Concerning a most famous lover of children—at least of girls—Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, I found some disappointing detail reported by his biographer, Morton N. Cohen; in Lewis Carroll, A Biography, Macmillan (1995), he wrote in Chapter 9, “The Man,” pages 300–301:

He was tightly bound up in Victorian values and decidedly class-conscious. Recounting to his brother Edwin an extraordinary backstage visit at the Haymarket Theatre to watch a group of child actors prepare for a performance, he wrote (March 11, 1867): “There was not much real beauty [in the little actresses], but 2 or 3 of them would have been much admired, I think, if they had been born in higher stations in life.” Commenting to Miss Thomson (January 24, 1879) on some draft sketches she had sent him, he objected to “the diameter of the knee and ankle” of one of the children she had drawn. “Still,” he added, “you may have got those dimensions from real life, but in that case I think your model must have been a country-peasant child, descended from generations of labourers: there is a marked difference between them and the upper classes—especially as to the size of the ankle.” Again he wrote Miss Thomson (September 27, 1893), after the Moberly Bells (Mrs. C. F. Moherly Bell was Gertrude Chataway’s older sister) agreed to allow her to use their children as models, asking her “to put them into a few pretty attitudes, and make a few hasty sketches of them. … These you could finish,” he added, “with the help of hired models. But hired models,” he insisted, “are plebeian and heavy; and they have thick ankles, which I do not agree with you in admiring. Do sketch these two upper-class children. One doesn’t get such an opportunity every day!”

On September 29, 1881, Charles made a new child friend on the beach, on Julia Johnstone, “who proved very pleasant and quite free of shyness. The mother is pleasant, but hardly looks a lady. I fancy the father is in business … but of course I shall not drop her acquaintance for that.” Weighing the wisdom of publishing a cheap edition of Alice, he concluded (March 4, 1887) to Edith Nash: “It isn’t a book poor children would much care for.” And writing to a lady friend in Oxford from Eastbourne, he complained (July 27, 1890): “The children on the beach are not the right sort, yet. They are a vulgar-looking lot! I should think there’s hardly any one here, yet, above the ‘small shop-keeper’ rank.”

On the day after telling an assembly of fifty or sixty girls “Bruno’s Picnic” and other stories at a school where Beatrice Hatch was teaching, he wrote her (February 16, 1894): “I should like to know … who that sweet-looking girl was, aged 12, with a red nightcap. … She was speaking to you when I came up to wish you good-night. I fear I must be content with her name only,” he added; “the social gulf between us is probably too wide for it to be wise to make friends. Some of my little actress-friends are of a rather lower status than myself. But, below a certain line, it is hardly wise to let a girl have a ‘gentleman’ friend—even one of 62!”

His argument, that lower classes have through many generations evolved physical features distinct from those of higher layers of society, is ludicrous if one knows that the 19th century bourgeoisie, including the intellectual middle class, arose from freed farmers and craftsmen at the end of the Middle Ages.

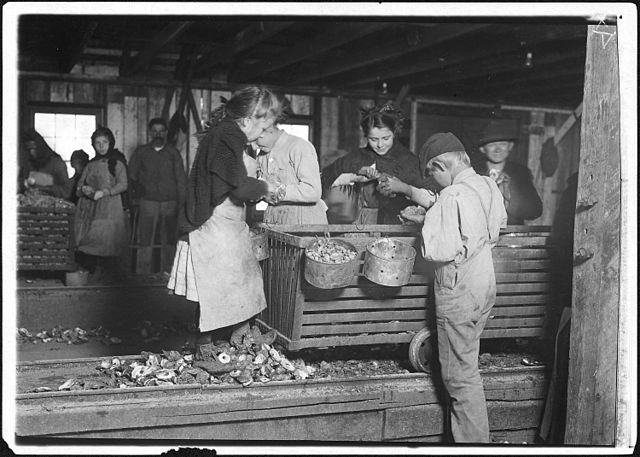

The writer Ernest Dowson showed a healthier attitude towards working class children. Managing the family business, a dry dock on the river Thames located in Limehouse, he could see workers’ children, and he recognized that it is only their later life as labourers that distorts their features. In The Letters of Ernest Dowson, edited by Desmond Flower and Henry Maas, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press (1967), one reads in Letter number 5 (11 January 1889), p. 25:

I have discovered an adorable child here, hailing from one of the three publics that surround us on either side—“which pleases me mightily” as Pepys would say. It is astonishing how pretty & delicate the children of the proletariate are—when you consider their atrocious after-growth. Of course it is the same in all classes but the contrast is more glaring in Limehouse. This child hath 6 years & is my frequent visitor, especially since she has realised that my desk contains chocolates.

Previously published on Agapeta, 2015/05/24.