The English writer Thomas Penson De Quincey (b. August 15, 1785; d. December 8, 1859) knew fame with his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, published anonymously in two parts in the September and October 1821 issues of the London Magazine, then released in book form in 1822. In 1845, De Quincey published Suspiria de Profundis, advertised as being a sequel to the Confessions. Then in 1856 he revised his Confessions, which became much longer. Since then, the two are usually published together, their complete titles being Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, Being an Extract from the Life of a Scholar, and Suspiria de Profundis: Being a Sequel to the “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.”

This book had an immense impact on modern culture. It influenced several writers and artists. Charles Baudelaire adapted in French, under the title Les Paradis Artificiels, the Confessions and part of Suspiria. The scholar Robert Morrison, in his article “De Quincey’s wicked book” (OUPblog, February 21, 2013), attributes to the Confessions the shift in attitude to opium that occurred in the 19th century: from a medicinal drug, it became a recreational drug; furthermore, he states that by mixing opium addiction with intellectualism and unconventionality, De Quincey, who was the first flâneur, created the counter-cultural figure of the bohemian.

In some way, before Poe and Baudelaire, Thomas De Quincey could be considered as the forerunner of the Decadents. He was also one of the pioneers of black humour, as witnesses his 1827 essay On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts.

In the section The Affliction of Childhood of Suspiria, De Quincey discusses at length his childhood and the sufferings he experienced during it, in particular the death of two of his three sisters. Baudelaire stresses that having been raised among women, in particular with elder sisters, a man like him acquires delicacy and distinction, a kind of androgyny, without which his genius would remain incomplete. This sensitivity to young girls shows itself in the section Preliminary Confessions of the Confessions, where De Quincey tells a moving story of a forlorn little girl who shared his misery, and whom he loved for no other reason than their shared wretchedness, for she possessed neither beauty, nor intelligence, nor good manners.

When aged about 18, De Quincey was homeless and his vagrancy led him to London, where he suffered hunger:

Soon after this, I contrived, by means which I must omit for want of room, to transfer myself to London. And now began the latter and fiercer stage of my long sufferings; without using a disproportionate expression, I might say, of my agony. For I now suffered, for upwards of sixteen weeks, the physical anguish of hunger in various degrees of intensity; but as bitter, perhaps, as ever any human being can have suffered who has survived it. […] Let it suffice, at least on this occasion, to say, that a few fragments of bread from the breakfast-table of one individual (who supposed me to be ill, but did not know of my being in utter want), and these at uncertain intervals, constituted my whole support.

This man allowed him to sleep in an nearly empty house, in which lived a poor and hungry little girl:

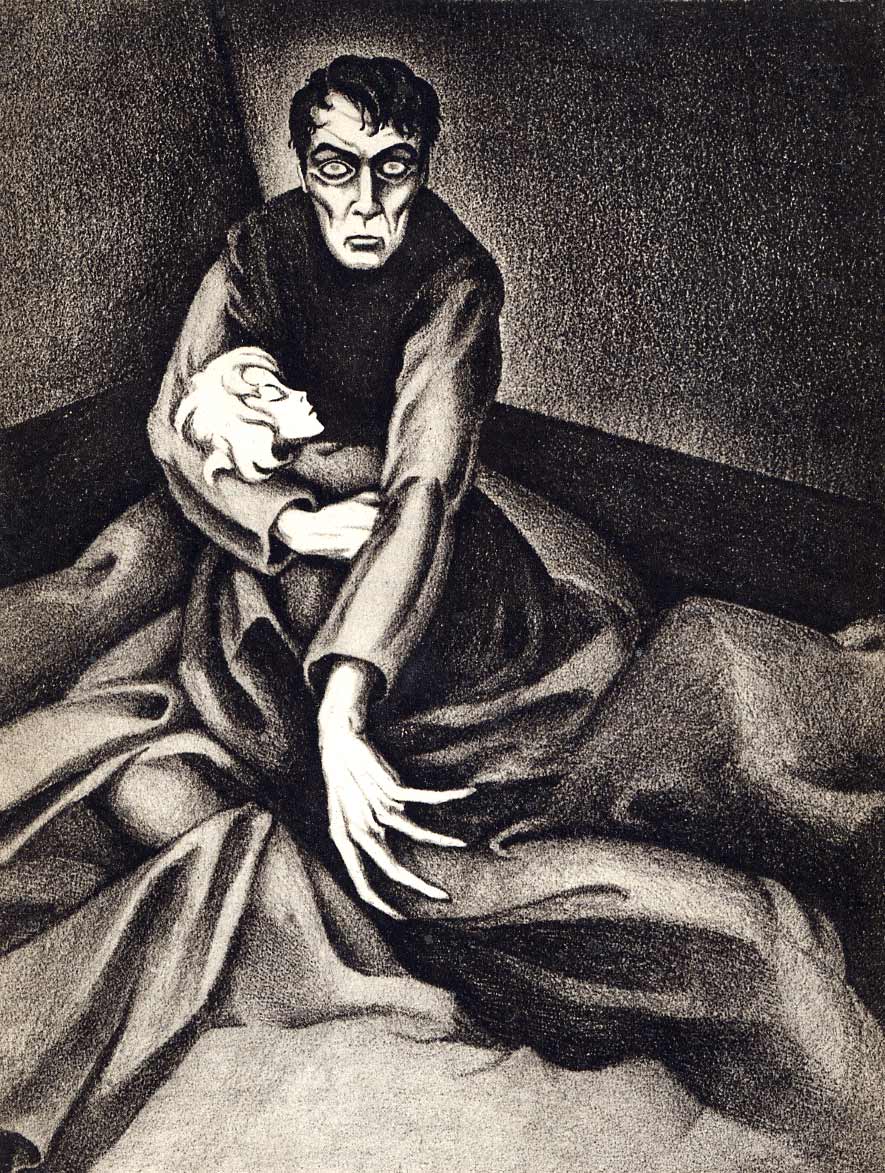

Latterly, however, when cold and more inclement weather came on, and when, from the length of my sufferings, I had begun to sink into a more languishing condition, it was, no doubt, fortunate for me, that the same person to whose breakfast-table I had access allowed me to sleep in a large, unoccupied house, of which he was tenant. Unoccupied, I call it, for there was no household or establishment in it; nor any furniture, indeed, except a table and a few chairs. But I found, on taking possession of my new quarters, that the house already contained one single inmate, a poor, friendless child, apparently ten years old; but she seemed hunger-bitten; and sufferings of that sort often make children look older than they are. From this forlorn child I learned, that she had slept and lived there alone, for some time before I came; and great joy the poor creature expressed, when she found that I was in future to be her companion through the hours of darkness. The house was large; and, from the want of furniture, the noise of the rats made a prodigious echoing on the spacious staircase and hall; and, amidst the real fleshly ills of cold, and, I fear, hunger, the forsaken child had found leisure to suffer still more (it appeared) from the self-created one of ghosts. I promised her protection against all ghosts whatsoever; but, alas! I could offer her no other assistance. We lay upon the floor, with a bundle of cursed law papers for a pillow, but with no other covering than a sort of large horseman’s cloak; afterwards, however, we discovered, in a garret, an old sofa-cover, a small piece of rug, and some fragments of other articles, which added a little to our warmth. The poor child crept close to me for warmth, and for security against her ghostly enemies. When I was not more than usually ill, I took her into my arms, so that, in general, she was tolerably warm, and often slept when I could not; for, during the last two months of my sufferings, I slept much in daytime, and was apt to fall into transient dozings at all hours.

This little girl served as a menial servant for the man who rented that house and on whose breakfast remains De Quincey fed himself:

During his breakfast, I generally contrived a reason for lounging in; and, with an air of as much indifference as I could assume, took up such fragments as he had left,—sometimes, indeed, there were none at all. In doing this, I committed no robbery, except upon the man himself, who was thus obliged (I believe), now and then, to send out at noon for an extra biscuit; for, as to the poor child, she was never admitted into his study (if I may give that name to his chief depository of parchments, law writings, &c.); that room was to her the Blue-beard room of the house, being regularly locked on his departure to dinner, about six o’clock, which usually was his final departure for the night. Whether this child was an illegitimate daughter of Mr. —, or only a servant, I could not ascertain; she did not herself know; but certainly she was treated altogether as a menial servant. No sooner did Mr. — make his appearance, than she went below stairs, brushed his shoes, coat, &c.; and, except when she was summoned to run an errand, she never emerged from the dismal Tartarus of the kitchens, to the upper air, until my welcome knock at night called up her little trembling footsteps to the front door. Of her life during the daytime, however, I knew little but what I gathered from her own account at night; for, as soon as the hours of business commenced, I saw that my absence would be acceptable; and, in general, therefore, I went off and sate in the parks, or elsewhere, until nightfall.

This house remains vivid in De Quincey’s nostalgic memory, as the place were he experienced utter misery, but also where he felt love for his little companion of misfortune. Unfortunately, he could not trace her …

Except the Blue-beard room, which the poor child believed to be haunted, all others, from the attics to the cellars, were at our service. “The world was all before us,” and we pitched our tent for the night in any spot we chose. This house I have already described as a large one. It stands in a conspicuous situation, and in a well-known part of London. Many of my readers will have passed it, I doubt not, within a few hours of reading this. For myself, I never fail to visit it when business draws me to London. About ten o’clock this very night, August 15, 1821, being my birth-day, I turned aside from my evening walk, down Oxford-street, purposely to take a glance at it. It is now occupied by a respectable family, and, by the lights in the front drawing-room, I observed a domestic party, assembled, perhaps, at tea, and apparently cheerful and gay;—marvellous contrast, in my eyes, to the darkness, cold, silence, and desolation, of that same house eighteen years ago, when its nightly occupants were one famishing scholar and a neglected child. Her, by the by, in after years, I vainly endeavoured to trace. Apart from her situation, she was not what would be called an interesting child. She was neither pretty, nor quick in understanding, nor remarkably pleasing in manners. But, thank God! even in those years I needed not the embellishments of novel accessories to conciliate my affections. Plain human nature, in its humblest and most homely apparel, was enough for me; and I loved the child because she was my partner in wretchedness. If she is now living, she is probably a mother, with children of her own; but, as I have said, I could never trace her.

Source of the citations: Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, and Suspiria de Profundis, by Thomas De Quincey, Boston: Ticknor and Fields (1868). A slightly different version (in particular with a different punctuation) is given by Wikisource.

Hoedh: Hymnus ( Neuroprogrammierung )

Previously published on Agapeta, 2018/02/13.