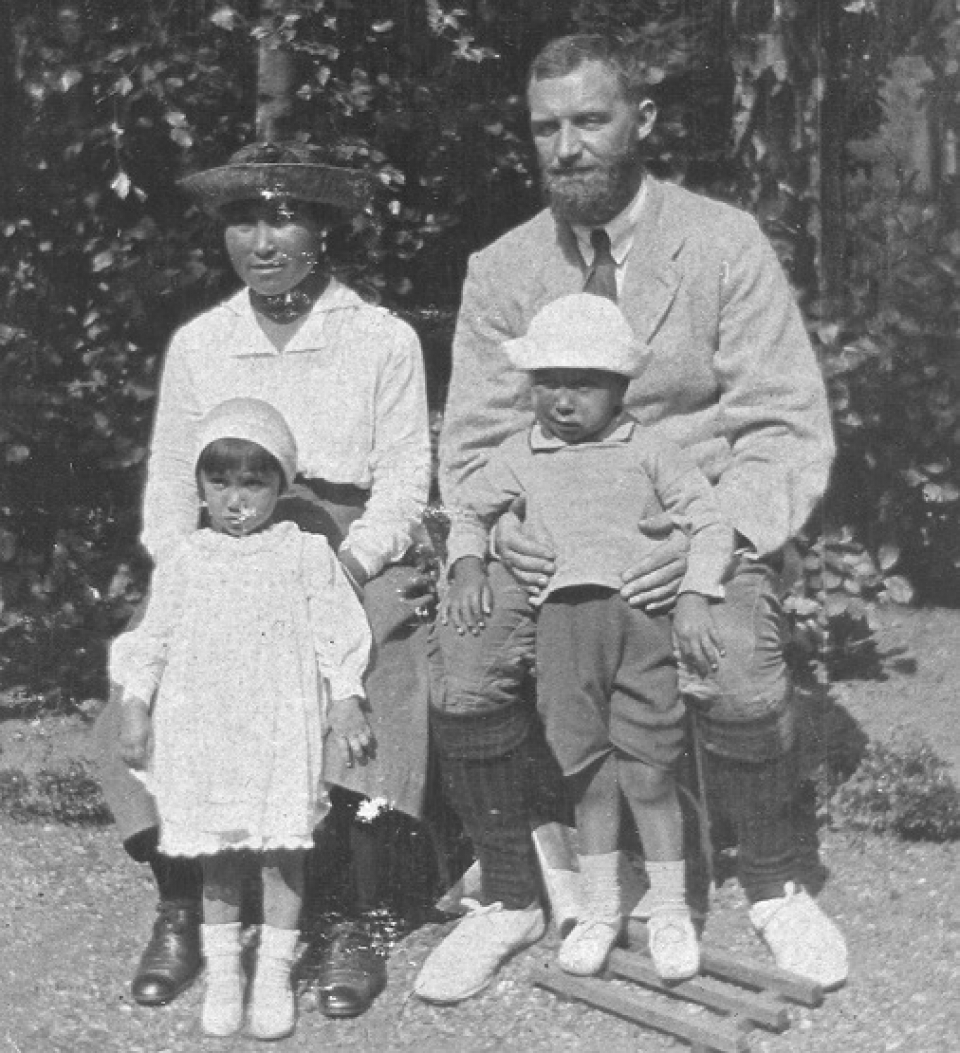

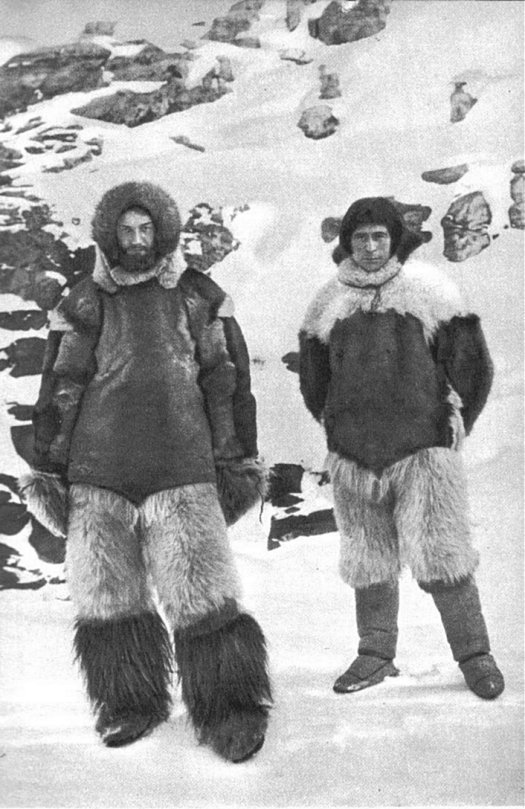

In a previous post I narrated how in 1911 the Danish explorer and ethnologist Peter Freuchen, then aged 25, married a 13-year-old Inuit girl, Navarana. They had a son, Mequsaq, and a daughter, Pipaluk, born in 1916 and 1918 respectively.

In 1920 they travelled together to Denmark, where they were invited to various official receptions, including one with the king.

Next day we had an audience with the King. The ruler of our country was gracious and asked Navarana the conventional questions: what did she think of Denmark, etc., etc.?

Navarana turned to me: “Is that man really the King we have heard so much about? How can he think for everybody in Denmark if he is stupid enough to suppose I have any opinions about this magnificent land after only one day’s stay?”

“What does she say?” asked the mighty man.

I translated freely: “Your Majesty, she thinks it is wonderful and grand!”

“I thought so!” said the King, and was content.

In Denmark Peter Freuchen contracted the “Spanish influenza” that devastated Europe after World War I, but he survived it. During his recovery, he invited Navarana to watch a ballet. Although she remained sceptical of Christianity, especially after a missionary had tried to seduce her while teaching her catechism, she remained sensitive to religious images.

Yet one night I took her to the Royal Theater to see a ballet, which was at that time the most celebrated in Europe. She was entranced. After we returned home and I went to bed she sat looking out the window. “Tell me the truth,” she said. “Were those real angels we saw in that church? If so, there must be some truth in that Jesus stuff.”

I was cruel enough to laugh, and it hurt her. I explained that we had not been in a church, but a place of amusement. The leading lady was certainly a lovely person, but positively no angel, and I promised Navarana I would take her to visit the woman, who was a good friend of mine, the next day.

We lost no time in calling upon Mrs. Elna, the ballerina, who was then one of the foremost dancers in Europe. She chatted with Navarana pleasantly, and gave her a large bottle of expensive perfume to take back to Greenland—it should have lasted at least a year.

Navarana was disappointed with Mrs. Elna’s obvious earthly bearing and said later that it would certainly have been nice if Jesus had such a theater where the doubters might go and be given a glimpse of the workings of heaven.

We gave a farewell ball for our many friends and all the Eskimos of South Greenland who now happened to be in Copenhagen. Navarana was a great success. She was so lovely and her happiness shone from her eyes. She wore the finest gown and bright, shiny new pumps. As this was to be her last public appearance in Copenhagen, she danced gaily the whole night. When the Hudson Bay expedition was over she would return and visit her Danish friends again. That was the plan, but it never materialized.

We drove back to the hotel after the ball was over. Her feet hurt her so badly she could scarcely hobble from the car to the lobby, and when she was finally undressed she could not sleep.

I awakened after a few hours and found her sitting with her poor, swollen feet in a basin, into which she had poured all of Mrs. Elna’s choice perfume. The perfume was, she said, the only thing she could feel. Water was worse than nothing.

“Whether she was an angel or not,” Navarana went on, “I thank her for the bottle. The stuff smells terrible, but it is wonderful for cooling sore feet.”

That was the end of Mrs. Elna’s gift.

In 1921, while Pipaluk remained in Denmark with Peter’s family and Mequsaq was at their home in Thule, in North-West Greenland, the “Spanish influenza” pandemic reached that island. Navarana fell sick while they were in South-West Greenland, on their way home, and she died there.

It was apparent by now that Navarana had Spanish influenza, the same disease to which I had fallen victim the year before. I did not leave her side, and got our good friend, Fat Sofie, to help nurse her. Navarana was thankful that I could be with her, though she was torn with anxiety for her children. She would have liked me to go up to Thule and see that Mequsaq was being cared for properly.

“Now both the babies are away from us,” she said, and asked me to tell her about little Pipaluk—how was she? what could she say? did she ever ask about her mother?

The next day Navarana was worse. There was no doctor in Upernivik at the time, and there was nothing more we could do for her. In the evening she asked me what I thought was the matter. Her head was buzzing with thoughts which came unsummoned, she said. It was ghastly to sit helpless and watch her fade away. I told her to try to sleep, but she could not.

After a while she began to talk about her visit to Denmark and the things she had seen there. That had been the high point in her life.

“But tell me the truth,” she said. “Was that girl an angel? She danced like one and looked like the pictures the missionary showed us? I never could figure it out or get it right.”

I told her again that it had only been a show, that she had not seen real angels.

“Then maybe one never has a chance to see them,” she concluded.

I admitted this might very well be true, and she lay still for a long while. Then she took my hand in hers and told me how happy she had been in having a husband who would talk with her as an equal. And finally she said that she was very sleepy.

I went into the kitchen to brew tea for her. As I sat and watched the water it came over me how much I loved her, and how much she had developed since our marriage. I don’t know why, but suddenly I regretted that my good friend Magdalene had not been in Denmark when Navarana was there, and that the two girls had never met.

Navarana was so quiet that I tiptoed in to look at her. As I watched, her lip just quivered. Then she was dead.

I would not believe it. I had somehow never thought of the illness as much more than a bad cold, but I called the young assistant, and he could only concur in what I saw before me.

My dear little wife was dead. I sat petrified. For the first time in my life I was in the presence of the death of someone close to me. My past life had been happy and carefree, and suddenly I found myself the father of two motherless children.

I had taken Navarana out of her natural life and surroundings. I hoped that she had been recompensed for what she had lost. But who knows? She was the bravest little girl who ever lived, and never would have complained about anything that came her way.

Fat Sofie took me to her house, and she and a friend made arrangements for the coffin and the funeral. I was almost unconscious of anything that happened, and had lost interest in everything. But soon something happened which brought me to life with a vengeance.

The minister in Upernivik, an undersized, native imbecile, came to me with the statement that, since Navarana had died a pagan, she could not be buried in the graveyard. No bell might toll over her funeral and, he was sorry, he could not deliver a sermon.

It was relaxing for me to be so furious. I told him to go to hell with his bells and his sermon, but my wife would sleep in the cemetery and not be thrown to the dogs. Still, he said, he had already warned his congregation of the horrible consequences of dying without baptism, and this was his opportunity to offer them an example.

I am glad that I did not strike him. I had the good grace only to tell him to get out and let me manage the service.

It was the most pitiful funeral I have ever witnessed. The workers of the colony acted as pallbearers, and I was instructed to pay them each a kroner for the task. I remember that I was angry at the blacksmith because he smoked a cigar during the procession, if such a word as “procession” may be used, since there were only four of us—Aage Bistrup, the manager, and his young assistant, both Danes, and myself, and then Fat Sofie, who made the only gesture of gratitude. She had fashioned a sort of bouquet from gaily colored Christmas tree decorations, and it lay upon the coffin with a silly-looking Santa Claus peeping through the ornaments.

Hidden between rocks and houses were the natives, terrified at the approach of this funeral procession which had not been solemnized by a minister nor sanctioned by the tolling of bells from the church. They dared not follow such a pagan to her final resting place, my little Navarana who had fed and entertained them whenever they visited her or she came to their houses.

Now, a few days before I wrote this, I read the gracious book written by Mrs. Ruth Bryan Owen, American ambassador to Denmark. Mrs. Owen was in Upernivik in 1934, and laid a bouquet of red flowers upon Navarana’s grave. It brought tears to my eyes to read of it, and reminded me of my rancor toward the church at that time.

I had a simple, beautiful stone carved to mark the grave, which is atop the cliff.

I realized all too well that there I left a part of my life—a part I shall always be thankful for. And Mrs. Owen, a lady with both heart and intelligence, made me realize once more that women from every locality, from any station in life, have certain common graces, and I bow my head.

Those were the sad tidings I had to relate to Knud when he returned from Thule. He had always adored the happy and helpful little Navarana. She made her own memorial in the clothes she had put together for our expedition. We had always counted upon her for so many things. The two of us climbed up to her grave and said good-bye for the last time, and sailed away to new chapters in our lives.

Navarana’s grave still lies in the cemetary of Upernivik, which seems to have beeen abandoned since. Note the ironic contrast between the good condition of the grave and the crosses lying on the ground, a reminder of the contempt of Peter and Navarana for the bigotry and hypocrisy of religious ministers and missionaries.

Here is a close-up of that grave:

Reference: Peter Freuchen, Arctic Adventure: My Life in the Frozen North (1935). Reprinted by Echo Point Books & Media (2013).

Previously published on Agapeta, 2017/05/31.

Fascinating content. Thank you for posting.

Does anyone know what happened to Mequsaq? Did he ever married, had children?

What happened to daughter of Pipaluk Freuchen, Navarana? Is she still alive?

So many questions… but no answers….

The previous post to which I link at the beginning has a link to a biographical record of Navarana:

https://www.geni.com/people/Navarana-Mequpaluk-Avigah-Marsauguq-Freuchen/6000000020560027238

and in it there is a link to the records of Mequsaq and Pipaluk (with dates of birth and death). Pipaluk became a famous writer of children’s books:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pipaluk_Freuchen