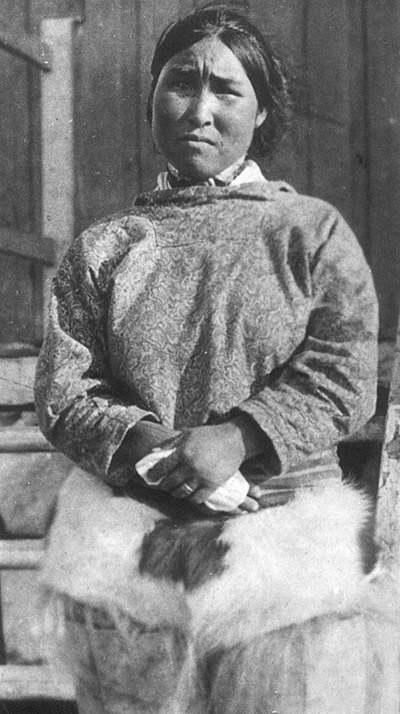

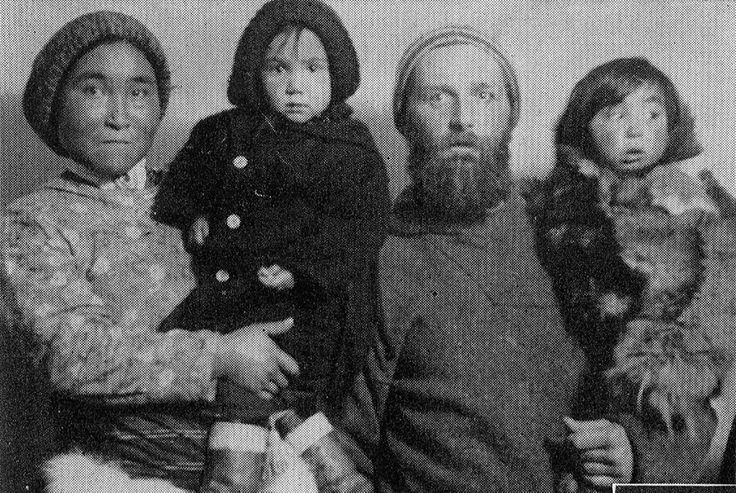

The Danish explorer and ethnologist Peter Freuchen (1886–1957) is famous for exploring the Arctic, in particular with his colleague and friend Knud Rasmussen (1879–1933). He lived many years in North-West Greenland, trading with Inuits, befriending them and adopting their way of life. In 1911 he married an Inuit girl, Navarana. Being born around 1898, she was thus aged approximately 13 at their marriage, while he was 25-year-old. Most biographies avoid mentioning this detail, referring to her as an “Inuit woman”. But in his 1935 book Arctic Adventure: My Life in the Frozen North he first mentions her as a “little girl,” and just after their marriage as “my little wife,” and in the 1961 book Peter Freuchen’s Book of the Eskimos edited by his widow Dagmar, he refers to her as a “little girl, just reaching the marriageable age,” but he also mentions that “Eskimo girls marry so very young that a girl will often continue to play with the other children right up to the time of her first pregnancy.”

Navarana’s life is a kind of Cinderella story. Before marrying Freuchen, she had known hunger and misery, she was dressed with rags, always had to work without end, but she always smiled and remained joyous. After her marriage, she became a well-dressed and affluent lady, with a high social status. Freuchen describes their first meeting in Arctic Adventure:

The evening before I left a young Eskimo girl came to the house bringing a pair of mittens she had sewn, saying that “someone” had left them at her home. I wondered, but I could not understand the reason for the gift. Later I learned that she had made them in order to thank me for some pieces of bread she had eaten one day while visiting us. I did not remember ever having seen her, but young girls are not especially conspicuous in that tribe. Fathers do not want to waste their fine animal pelts on grown girls. It is up to their future husbands to dress them, since a husband is always anxious to have his wife look well and not disgrace him. […]

This girl was dressed in dogskin pants, so disgraceful in appearance that they considerably restricted her visiting. Yet nothing would persuade her to request better material from her mother. She also wore an old coat of her mother’s, and most of the time she carried a little brother about with her in her hood. The mittens she brought me were none the less warm, and I bought her some fine presents in the south.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 45

After their marriage, she told him about the horrible hardship of her childhood:

Navarana’s own life had been a blood-curdling saga of the Arctic. As a small girl she had lived with her parents on Salve Island. One of those inexplicable epidemics that so pitifully ravage a primitive race struck the people, and on the island where they lived only Navarana, her mother and her small brother were spared. They had no meat to eat and were forced to butcher their dogs for food. When this source of supply was exhausted they ate their clothes and dog traces and anything available. The little boy was about three years old and was still nursing. The mother soon had no milk left, and the child in a frenzy of hunger bit the nipple off her breast. Then, seeing no hope of keeping him alive, she hanged him while Navarana looked on. The mother’s grief, Navarana told me, was worse than the sight of the dead child, and she swore to her mother that she did not want to die, no matter how hungry she was, but would remain to comfort her.

Navarana told me that she ate grass and the excrement of rabbits and chewed on the tatters of old skins and, with the fall ice, Uvdluriark arrived on his sledge and took them both to his house.

After a couple of years Navarana went to live with her grandfather and grandmother. Her grandfather, Mequsaq, was a veteran of great dignity and experience, and he lavished all his affection upon her. While living with Mequsaq she had the good fortune to escape a siege of starvation which wiped out thirteen others at Cape Alexander. This had occurred the year Mylius-Erichsen and Knud Rasmussen were there for the first time.

The old man and his wife and Navarana at the last found only two others alive, Kullabak and her son, Kraungak. They took the boy along with them (there was not room on their sledge for Kullabak), and when they reached the next community, left Navarana and Kraungak in a shelter while they went out to look for walrus. They got one, rescued old Kullabak and saved all their lives. Navarana told me that she remembered only one incident of this experience: while she and Kraungak waited for the old people to return, the boy, whose feet were frozen, cut off one of his little toes with a knife in order to impress her. He said it didn’t hurt, but she could never forget it.

— Arctic Adventure, pp. 144-145

Before marrying Freuchen, Navarana was called Mequpaluk. In the Book of the Eskimos he calls her Mequ and tells a similar story:

At the Thule settlement near my trading station, I began to notice a little girl who was wretched to look at, dirty, and with clothes made partly of dogskin, partly of worn-out hand-me-downs. Her mother, Kasaluk, had had two children with her first husband. The one, a little boy, she had to kill during a hunger period, but the girl, little Mequ, had “found life sweeter than death” even under those circumstances, so the mother allowed her to fend for herself. She survived and later had gone to live with her grandparents up north. Then Kasaluk was married to Uvdluriak, the great hunter at the settlement, and Mequ had been brought down to take care of her younger half-brothers and half-sisters.

The little Mequ had only rarely visited our house. But once—while she was there—I gave her some bread, which was a great delicacy to her. She was happier than any Eskimo girl before! And a few days later, she came with a pair of mittens she had sewn for me. She just laid them down in front of me and said: “To express thanks for the bread!” Then she was gone again, as quietly as she had come! She was shy and not used to speaking to important men without being asked!

— Book of the Eskimos, p. 102

In Arctic Adventure, Freuchen narrates his first conversation with that shy girl, who appears as a fleeting form in the polar night:

Yet in the group there was one face I missed—that of a certain young girl. I inquired about her, the stepdaughter of Uvdluriark, and all the natives were amazed and wanted to know why. I explained that I had brought something to pay her for the mittens she had given me. Everyone snickered, and I realized I had done something that was simply not done: I had mentioned and asked for a girl.

But next day I met her as she walked on the ice with her little brother slung on her back. When she saw me she hid behind an ice hummock. I started round to find her but she ran as fast as she could go. She was hampered by the child on her back, and it was easy for me to catch her and hold her.

“Why do you run away?” I demanded.

“I don’t know.”

“Are you afraid of me? You need not be!”

“No, I am not afraid, but someone told that you had inquired for me yesterday before everyone. Therefore I was embarrassed!”

“I forgot your name—what is it really?”

“Oh, I am nobody, just the most ugly and foolish girl in the tribe.”

“I don’t think so, but what is your name?”

“I don’t know.”

“You mean you don’t know your own name?”

“No, I never heard it.”

“Nonsense,” I persisted. “Of course you know your name. Why won’t you tell it to me?”

“Others can tell it to you, but it is not important.”

“I brought something back for you, something you will like.”

“Oh, no, don’t give me anything,” she begged. “Give it to somebody worth giving things!”

And while I looked about me in desperation for a means of breaking through her self-abnegation, she made a quick movement and disappeared in the dark.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 95

He met her again and noticed her devotion to her younger brothers:

I stayed with the family of Uvdluriark, whose young step-daughter, Mequpaluk, had given me the mittens. She repaired my boots and mended my clothes when necessary. She was a handsome girl, but her own clothes were so shabby that her body showed through in many places. It was strange to see her in a household which, aside from herself, was so affluent. But her father would have it no other way. “When she is married,” Uvdluriark grinned, “it is up to her husband to dress her.” She was an excellent worker, and her devotion to her younger brothers was touching. Whatever I paid her for her services she always gave to them, and would never eat at my house without hoarding the scraps for the small ones at home.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 121

Then they had a moving conversation about the moon, which led to their sharing their first secret (here the word angakok means conjurer or sorcerer):

When we were ready to return home the ice was bad, and I had to take Uvdluriark’s stepdaughter along with me. It was then that I discovered what an extraordinary person she was. There was no laziness in her; to work was her pleasure. When we halted to rest the dogs, she always untangled the traces before the animals had a chance to lie down. Whenever I needed anything she foresaw and, if possible, fulfilled my need. She was the only girl I ever met among the Eskimos who really cared for flowers and birds.

We drove home in the night, though it was daylight. We could see the moon, but it was pale and unreal before the sun. I looked at it and remarked that when the moon was only half as large it was easier to examine it with my field glasses. She looked at it carefully through my glasses. I have always been too proud of my little knowledge, and I started to tell her about the mountains on the moon which she could see through the glasses. She stopped me:

“Mountains? The man, you mean?”

I smiled down upon her from the great height of my learning, and told her that there were indeed mountains upon the moon.

“But then,” she asked, “what about the man up there?”

“There is no man in the moon.”

I was surprised that anyone should really believe the myth, but she explained that her grandfather, who was a wise old man, had told her there was a man in the moon. Her mother believed it too. How could one believe anything the angakoks said if they lied about the man in the moon?

This she asked in a very modest way, and as sincerely and simply as possible I assured her that they were wrong—there was no man in the moon. From that day forward there was a secret bond between us. I was to her the man who knew everything, and I tried in every manner possible to live up to the great faith and trust of her clean and innocent soul.

When we reached home we parted—she to run to her mother’s tent where she spent more than twenty hours a day caring for her small brothers and keeping house.

— Arctic Adventure, pp. 123-124

He met her again, one day that he had been visiting the crew of a European ship with other Inuits, in particular women who traded their charms to sailors in exchange of gifts.

Mequpaluk, Uvdluriark’s stepdaughter, ran down to the beach to receive us—she had been left behind, as usual, to care for the children and the dogs. I heard her remark that she had been crying because she wanted so badly to go with us—but now she was happy enough to get something for the children from our loot.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 135

Now he describes his sudden marriage. Working at his home was a married woman, Arnanguaq, whose husband had clearly stated that he did not want to engage in wife-swapping. Thus in order to avoid any gossip, little Mequpaluk was invited to spend the nights in their house:

To circumvent any whisper of scandal Arnanguaq invited Mequpaluk to spend the nights with her. Each evening after the girl had done all her chores at home she came running down to the house. Her clothes were still disgraceful, her boots almost soleless, and her stockings furless. But she was always in the best of humor and our room became a cheerier place when she entered it. She had a trick of recounting her experiences so quaintly that everyone laughed with her, and each night we awaited her arrival with impatience.

Finally one evening when she came Arnanguaq was absent, and I told Mequpaluk that she had better stay with me. She looked at me a moment and then remarked simply:

“I am unable to make any decisions, being merely a weak little girl. It is for you to decide that.”

But her eyes were eloquent, and spoke the language every girl knows regardless of race or clime.

I only asked her to move from the opposite side of the ledge over to mine—that was all the wedding necessary in this land of the innocents.

Next day she wanted to know whether she was to return to her home or not, and when I said no that was final. A few hours later one of her brothers came to ask why she had not come home. She said:

“Somebody is occupied by sewing for oneself in this house!”

The boy was startled but said nothing, and turned on his heel to race from house to house with the news. After a few hours sledges hurried north and south to tell what had happened and to hear firsthand the comments of the neighbors.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 141

In Book of the Eskimos he gives a different story, stresssing how the idea of marriage slowly came to his mind:

One day, when I passed by the tents with Knud, Mequ was sitting outside with her little brother.

“How sweet she is, really,” said Knud. “If I were ever to marry up here, she would be the only one along the whole coast, from the south and right up to here, that I could imagine would be intelligent enough, and clever enough, and beautiful enough!”

I didn’t ponder the matter; but for the first time the thought of marriage occurred to me. Knud was right. This business of borrowing another man’s wife was not exactly what we ought to promote in the district, and therefore we shouldn’t participate in it, either. It never came into Knud’s mind to reproach me about the conduct of my private life, but his remark hit home with me. This little girl, just reaching the marriageable age, seemed really so pure and fine to me—in spite of her dirty dogskin pants and the torn kamiks. Her smile and good cheer covered it all. Also, it was known that her stepfather could furnish her with magnificent skins if he wanted to. But this just wasn’t done. Because of the hunger period some years before, during which many girls had been killed, there was a lack of women among the Polar Eskimos and several young men had already been to see Uvdluriak.

One day we heard that Samik, a feared and often wrathful man, had raped Mequ while his wife happened to be visiting, us. It caused quite a bit of excitement, but nothing could be done. The missionaries remained silent when their own little flock wasn’t concerned—but it happened to be one of them, a man named Seckman, who brought me the bad news. He asked if we shouldn’t do something. We then went to see Uvdluriak, but he didn’t think that any harm had been done. He had no intention of starting a feud with his neighbor. Shouldn’t people rather laugh at such a witless hunter like Samik, who preferred an immature girl to his own excellent wife?

Later that winter, I was staying alone in our house with a servant woman, Arnanguaq, who took care of the lamps. Everybody else was away on trips. Arnanguaq was married to our handyman, Minik, who happened to take the position that “he did not want to make appointments for exchange of women” with anybody. But even if Arnanguaq did not fear any attack from my side, she invited Mequ down to the house for the night, so that she wouldn’t be alone with me.

We undressed and went to bed. Our lamps were burning low, the wicks had been made small so that the blubber could last until morning. Suddenly, in that romantic half-dark, I was possessed by a power stronger than myself. I threw my skin covers aside, reached over and grabbed the young girl, and swung her over to me on my bunk. She didn’t say a word, and neither did Arnanguaq.

Thus I was married and, to the extent possible for an explorer, settled down. Mequ was so small and fine of build. Her hands were soft, as if she had been manicuring them all her life. But the night of our marriage she had had to do a lot of dirty work, and her entire body was filthy, her clothes too miserable for description. My remembrance of the night is somewhat misty, but in the morning I told her that I didn’t intend to let her go home, that I wished to keep her with me.

Her reaction was a little less lyrical than I had expected: “Then somebody else must bring my mother the needle that I borrowed from her!”

She pulled a needle out of her hairtop, where she had kept it tucked away. Possibly it was only a message; Arnanguaq went with the needle. In the meantime, we went to the big house to have breakfast. Emilie Rosbach, the missionary’s wife, had the food ready. Naturally, she was much too well-bred to say anything. I put Mequ down at the table by my side, and there she sat, for she didn’t dare to move. She got a fine cup, she got bread and tea. There was sugar to put in the tea, but as she didn’t seem to think that it was proper for her to take any of it, I put two teaspoonsful in her cup. In those days a clearer announcement of marriage couldn’t be made in Thule.

I was aware that I had to guard Mequ for some time. Since I had not abducted her properly, as any decent groom would, it would be a while before people realized that it was a permanent arrangement. So she went with me wherever I went, except that I couldn’t take her with me out to my caches to fetch supplies; her clothes just weren’t good enough for even short sled trips. Pants of dogskin, the greatest shame to a man! But it didn’t take long to make up for that, for we had plenty of foxskins. I didn’t have any sealskins for kamiks, however, so she had to go to her mother to get them. She went with rich gifts: the little children got canned milk, the mother became the proud owner of a beautiful pair of scissors and a royal supply of thread. Mequ was now completely rehabilitated after her former miserable state—which was by no means due to Uvdluriak’s stinginess, only to custom. Besides, her husband now had the joy of seeing his little wife grow more well-dressed and civilized from day to day.

— Book of the Eskimos, pp. 102–105

It took some time for other people to take that marriage as more than a temporary arrangement:

Many years later I heard the term “going native,” but it did not occur to me then that that was what I was doing. I did know that my marriage to an Eskimo girl made a final breach with the world I had known as a young man, but I had already left that world far behind. Navarana was immediately accepted as my wife wherever we visited in Greenland, and no one worried over the duration of our union. Not until long afterward, after our two children were born, did any of the natives admit to me that they had not at first taken our marriage seriously. Even Navarana’s mother had thought it but a casual arrangement, and that Navarana would soon be sent home.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 144

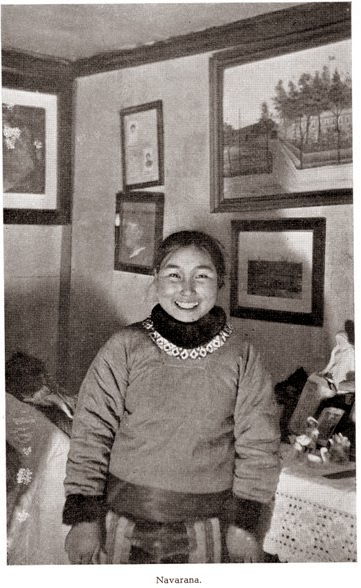

After her marriage, Mequpaluk adopted her second name, Navarana. According to Book of the Eskimos, this happened at Christmas:

The Eskimos commonly have several names, of which one is the calling name. Often the calling name is changed in order to mark a great event or turning point in the person’s life. At Christmas, shortly after our wedding, Mequ decided to use one of her other names; she was now to be spoken of as Navarana—“in order that some greater ability, hitherto concealed, might appear in her.”

From then on she was called Navarana.

— Book of the Eskimos, p. 107

But in Arctic Adventure he says that it happened the next evening:

The next evening my little wife asked me to come down to the beach with her so that we could talk alone without a roof over us. She said that she had spent the day in speculation, and she had decided, now that she was married to a white man, to use one of her other names. (Also, Odark’s wife, Mequ, had died recently, and the name “Mequpaluk” could not be spoken any more.) She had been too frightened, however, to change her name without consulting me.

I agreed that she should take another name, and from then on she was known as “Navarana” over all Greenland.

The first thing was to secure a wardrobe for her. Now she had plenty of furs to select from, and she hired several friends to do the sewing. There was no thought of actual payment as, Navarana told me, the sewers were delighted with the privilege of sitting in our house and listening to everything that was said. Their reward was in being able to tell what they had seen and heard.

We fixed up our room considerably and, when I came home with my first seal after our marriage, we invited all our neighbors to a feast. Still not one word was said of its being an unusual occasion.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 142

As Freuchen traded European goods for furs, he had plenty of them to give Navarana decent clothes:

When I returned home I began to appreciate the woman my wife was going to be. She still wore her rags, but her new boots were finished, and she looked incongruous in pure white, long boots with bearskin emerging from the tops and giving way to pants which would scarcely hold together. But next day the pants were replaced with fine new ones, and then she boasted the best raiment in the tribe.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 143

Their marriage rejoiced Freuchen’s friend Rasmussen, who congratulated him:

When we reached Thule, Knud Rasmussen was there before us. He had, of course, already heard that I was married, and he met us with the warmest congratulations. He told me that there was no other girl, from Cape Farewell to Thule, who was good enough for me.

— Arctic Adventure, p. 152There was no great excitement until Knud returned home. Rasmussen wasn’t a man to let a wedding just pass by. He sent word north and south, east and west, that with the next full moon the wedding would be celebrated in the grandest manner. This was a little against people’s taste, though. They found it immodest and a little bit tactless to blazon abroad that two young people now had agreed to stick together. What concern was it to others?

But the feast had to be great. I was myself ordered to deliver everything I could, especially eggs from my caches. So I made my first sled trip with Mequ, and we stayed away for a few days. Only then did I discover what I had been missing. On a sled, a Thule woman is as good as a man. She arranges the dogs, she swings the whip expertly, and she helps to pack and secure the load. Her cheer lights up the darkness! We were staggering around in the Polar night to find my depots, but we had a wonderful time. For Mequ it was the introduction to an entirely new life in which she, for the time being, remained a bit lost, but was very happy.

— Book of the Eskimos, p. 106

From now on, Navarana was an important lady, married to a rich trader who provided all European goods that made Inuit life easier. She could invite other ladies for coffee, or have guests eating in her house:

Our wedding feast was a great success. Knud had announced that he wanted to see who could bring the most and the best, and the celebrations finally amounted to several days’ sumptuous eating. It wasn’t quite easy, at first, for Mequ to be hostess to older women who had known her since she was born. She had been fatherless, and even if she lived with the old Mequsaq, she wasn’t as well protected as were the children of great hunters. Now she was the one who had the right to call out that boiled meat was ready, and to say that she hoped the guests would eat well to get her pots empty, so that she could fill them up again. Vivi and Emilie, two mature women, had to step into the background, and there were some frictions.

— Book of the Eskimos, p. 107

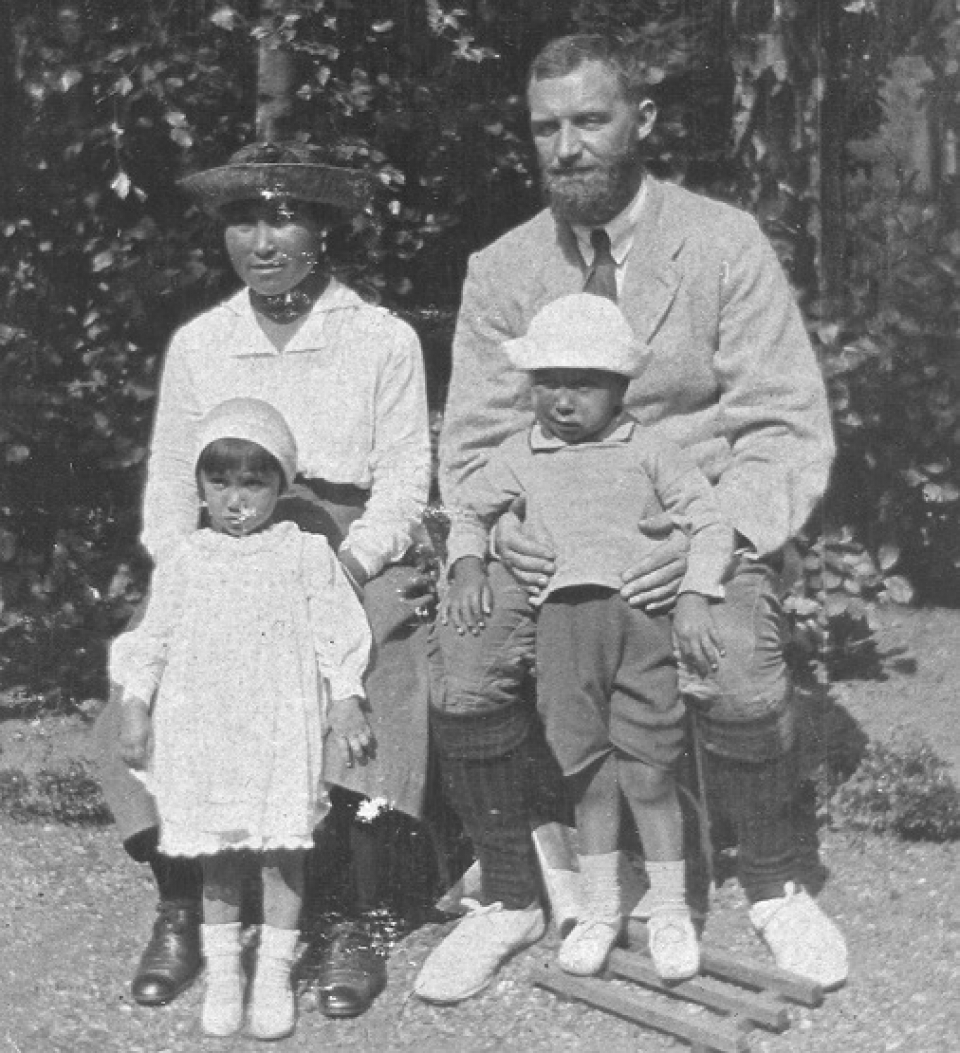

Their marriage was happy and loving. Peter and Navarana Freuchen had two children, a son Mequsaq (1916–c.1962) and a daughter Pipaluk (1918–1999), who became a writer. Navarana died in 1921 in the “Spanish influenza” pandemic that swept over the world.

Today, a sexual affair between a 25-year-old man and a girl aged 13 would be considered as child sexual abuse. And their marriage would be unthinkable. In 1958, the marriage between the 22-year-old singer Jerry Lee Lewis and 13-year-old Myra Gale Brown provoked a scandal, and his musical tour had to be cancelled. But hings were different in the past. In 1917, 21-year-old Paul Onesi married 13-year-old Mary Corsaro, they became the longest-married couple in the United States and were listed in the Guinness Book of Records: when Paul died in 1998, they had been married for over 80 years.

References:

- Peter Freuchen, Arctic Adventure: My Life in the Frozen North (1935). Reprinted by Echo Point Books & Media (2013).

- Dagmar Freuchen, editor, Peter Freuchen’s Book of the Eskimos, The World Publishing Company (1961).

Previously published on Agapeta, 2017/03/19.

In The Book of the Eskimos, the author describes Navarana as “this little girl…just reaching marriageable age”, which he subsequently indicates is about 12 years old. Then Navarana is brought to the igloo where he is staying with another Eskimo woman, so that this other woman wouldn’t have to fend off sexual advances from him. He says the three of them “undressed and went to bed. Suddenly, in that romantic half-dark, I was possessed of a power stronger than myself. I reached over and grabbed the young girl, and swung her over to me on my bunk.” He has sex with her, and says “Thus I was married.” He does mention that “She (Navarana) didn’t say a word, and neither did (the Eskimo woman).” Presumably this means that neither of them protested, and he offers this to the reader as evidence of consent, but Eskimo women were regularly beaten by their husbands in public, and were expected to service any man their husband saw fit to share her with, so it’s hard to see how their silence represented consent. I felt sick reading this. What does consent mean, in a culture where the men consider the women to be “mindless”, and “property”, and it is “beneath their dignity” to give any attention to his woman’s real needs? What did consent mean, for this 12-year old girl who’d already seen her younger siblings killed to avoid death by starvation, and who’d been marinating in this culture since infancy? She lived in rags, because her stepfather would never have been expected to provide better for her, even though he could well afford to do so – because “it just wasn’t done”. She worked “over twenty hours per day” taking care of her younger siblings. She’d already been raped a few months prior, about which “nothing could be done” according to the author. No doubt she was already well understood the lay of the land, and knew that a white man raping and possibly marrying her was a big step up from where she was. He also indicates that “during that period I had become more and more Eskimoic”. I suppose all of this should tell us how powerfully affected we all are by culture; transgressions he would never have dreamed of in Denmark are just how you handle your horniness in Eskimo country. “Suddenly I was possessed by a power stronger than myself”, said every man everywhere who suddenly raped a woman. What an abdication of self-responsibility. I do believe that he also loved her, and that he had many wonderful qualities. But I felt sick reading this. I have a lot of respect for his respect for Eskimo culture, but there is example upon example in his own book of the complete domination by Eskimo men of Eskimo women, and he fed right into that. I finished the book feeling grateful to not have been born an Eskimo girl, nor that I ever had to hope that some high-status man might rape me and thus greatly improve my standing in the world.

Your presentation of Eskimo culture and of Freuchen’s behaviour is just a caricature. I have read both Arctic Adventure and the Book of the Eskimos, and I give their two slightly different accounts of his marriage. Neither of these says that he had sex with her on that night, and there is no hint of violence: so I see no rape. From both books one sees that Navarana was a strong woman who knew what she wanted, so she would have resisted rape. On her deathbed, she thanked Freuchen for having treated her as his equal: that is not what one says to a rapist. Although in principle Inuit society was male-dominated, in practice it was egalitarian, so women had their word and could resist. Before colonisation, Inuits had a casual approach to sex, and children were exposed from infancy to sex acts and were free to play sex. Thus a girl aged 12 understood sex very well and could make informed decisions about it. That society has nothing in common with present-day USA, which has lived in centuries of sexual bigotry and is since 45 years in a moral panic about children and sex.

Well told. I would say to Kristen Holmes that her response in a very insular and colonial response. You replied thoughtfully and well.

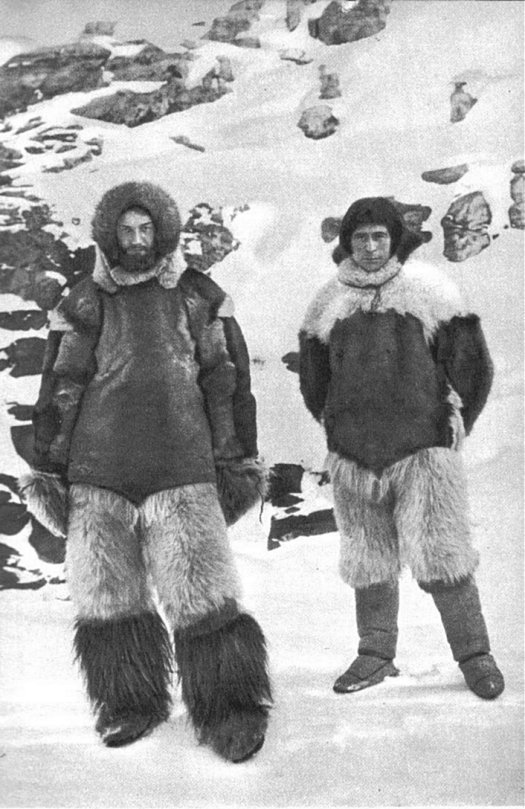

The first photo is misidentified. The picture was taken by Therkel Mathiassen on the Fifth Thule Expedition, and is of Arnarulunnguaq (left) and Aqattaq (right).

You mean the second photo? The first photo, after the title, is of Peter and Navarana.