Marjory Fleming was a Scottish child of the early 19th century, who died of meningitis one month before her ninth birthday and got posthumous fame from her writings: three journals, several poems and letters.

She was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland on January 15, 1803, the third child of an educated middle-class family. In 1809 (at age nearly 7), she was sent to live in Edinburgh in the care of her mother’s sister, Marianne Keith, whose daughter Isabella, a young woman in her early twenties, took charge of Marjory’s education—b.t.w., Marjory’s mother and elder sister were also named Isabella. Apart from a possible trip home in the autumn of 1810, she remained there until July 1811.

A strong affective bond developed between Marjory and her cousin, who showed herself a patient and careful educator. For the little girl, she became like a mother figure; indeed, in some letters to Isabella, Marjory called her “My Dear little Mama” or “My Dear Mother.”

It was probably Isabella Keith’s idea to have Marjory write a journal, in order to survey her progress in handwriting, spelling and punctuation. This journal is made of three notebooks, ranging from spring 1810 to spring 1811. Upon her return to her family in Kirkcaldy by the summer of 1811, the journal ended. She missed badly her cousin, as shows her letters to Isabella, but the two would never meet again. In November 1811 she fell to an outbreak of measles, from which she seems to have recovered, then became ill from “water in the head,” apparently meningitis, and died on December 19, 1811, a little less than one month before her ninth birthday.

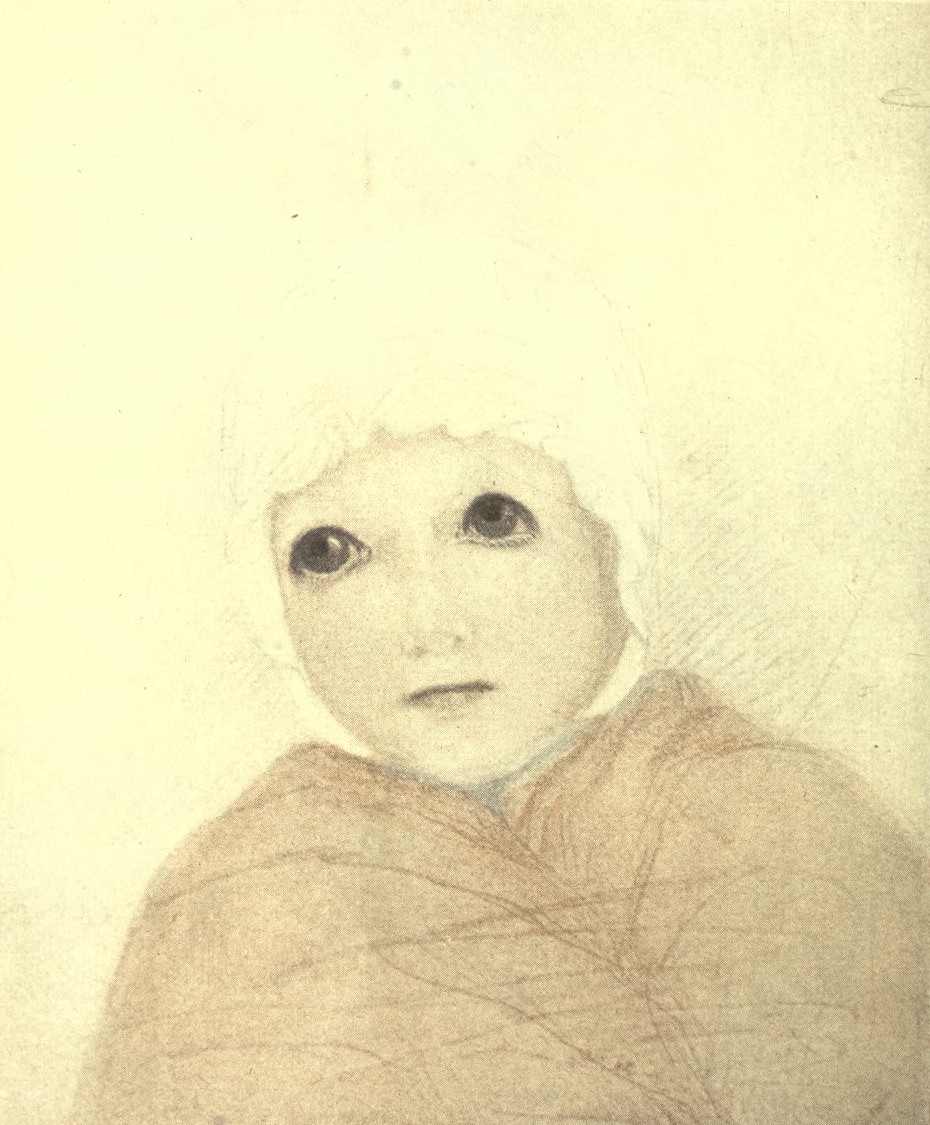

Soon after this, Isabella Keith returned Marjory’s papers to her mother, and at the request of her father she painted a watercolour sketch of the girl from memory. They remained in private hands until 1930, when they were donated to the National Library of Scotland.

In her three journals, Marjory tells pell-mell about various things, the weather, the events of life, her feelings for people, the books she read, all mixed with moral maxims and general considerations. She shows herself a witty girl and an avid reader of poetry and literature. But her spelling often remains faulty, which sometimes makes a funny reading.

She confesses openly her bad temper and unruly behaviour, in particular her violent tantrums, to which Isabella always responds with calm and patience. In the first journal, Isabella made her copy “I have been a Naughty Girl,” and in the second journal Marjory describes several episodes of her trying her teacher’s patience:

she never whiped me but gently said Marjory go into another room and think what a great crime you are committing and letting your temper git the better of you […] she never never whip me so that I thinke I would be the better of it and the next time that I behave ill I think she should do it for she never does it but she is very indulgent to me but I am very ungratefll to hir

Later, she says “I hope I will be religious agoin but as for reganing my charecter I despare for it,” then “Every body just now hates me & I deserve it for I don’t behave well.”

Her writings remained unpublished for 47 years. In 1858 the London-based Scottish journalist H. B. Farnie, who was shown the journals by her family, published in the Fife Herald long extracts from them, interspersed with sentimental accounts of her life; these were reprinted as a booklet, Pet Marjorie: a Story of Child Life Fifty Years Ago. He is responsible for spelling her name Marjorie and attaching it the nickname ‘Pet’. In reality, her real name was Marjory, and her family nicknamed her Maidie or Madgie, while Isabella called her Muffy.

About 1863, Marjory’s younger sister Elizabeth Fleming, born in 1809 (who was thus aged two when Marjory died), corresponded with a Dr John Brown MD of Edinburgh; she wrote him that her aunt Marianne Keith and the writer Walter Scott “were on a very intimate footing,” and that he presented Marjory with children’s book. In an 1863 article in the North British Review, John Brown claimed thus that Walter Scott admired Marjory’s poems. Then he published in 1864 his own version of her life, with more excerpts from her journal.

Brown’s book Pet Marjorie presents a typically “bowdlerised” version of the journals, with many inaccuracies, and censoring some of her language because it seemed inappropriate for a girl of her age. It also contains fanciful accounts of events of her life, such as a close literary and affectionate relation between Marjory and Walter Scott. The book obtained an immense success, the theme of the child prodigy meeting a tragic early death appealed to Victorian sensibilities, and it also benefited from the then immense popularity of Scott. Her fictionalised biography was repeated years later by further authors, such as Lachlan Macbean. Brown’s story was finally demolished in 1947, when the scholar Frank Gent established that Marjory and Scott never met; in fact, Scott never mentioned Marjory in his correspondence.

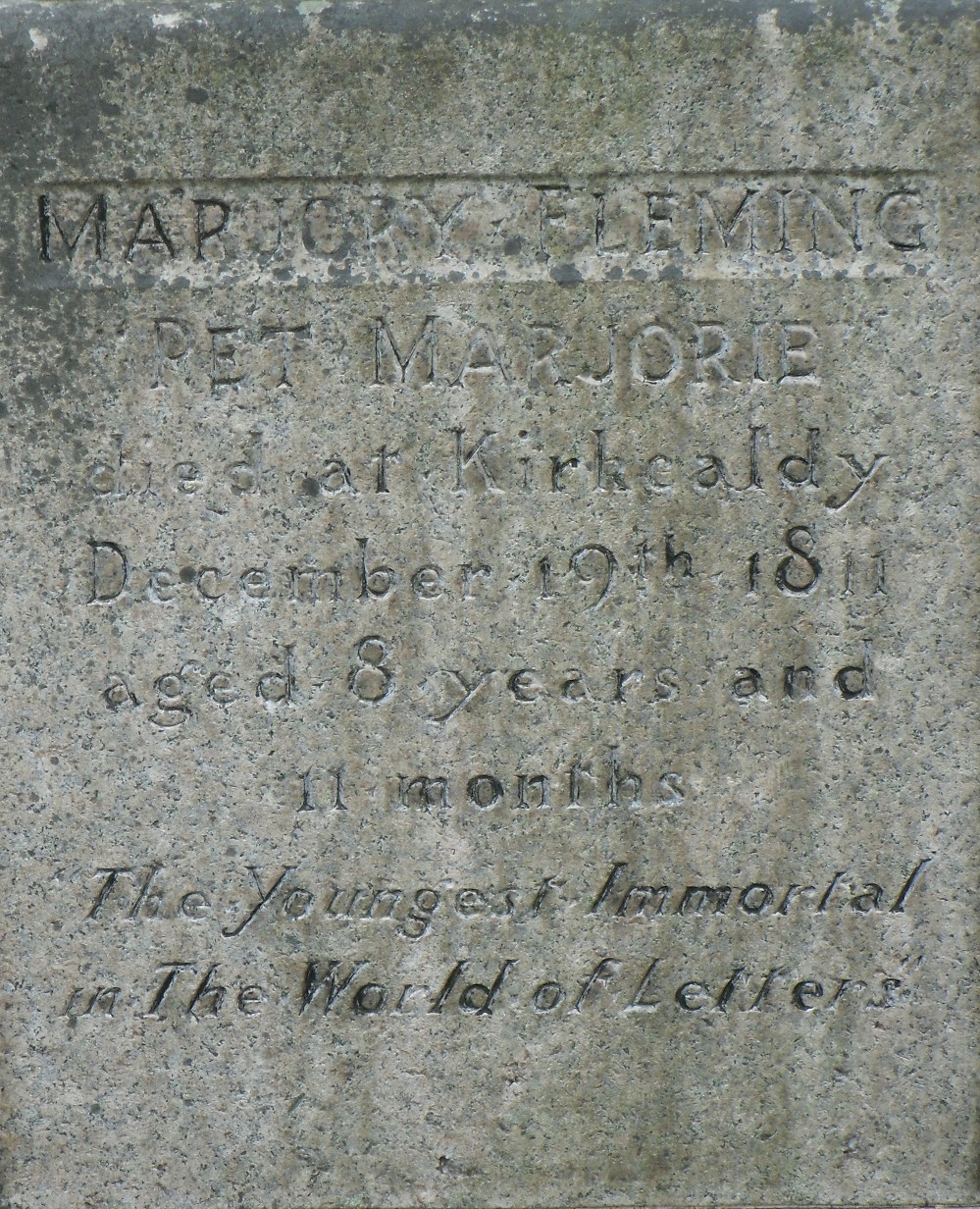

Following the acquisition of Marjory’s papers by the National Library of Scotland in 1930, a complete and accurate edition of her journals appeared in 1934, first a collotype facsimile by Arundel Eisdale, then a transcription by Frank Sidgwick. Since then, she has become a kind of Scottish national treasure, and the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson is credited with calling her “the youngest immortal in the world of letters.”

There is in Brae Park Road, Edinburgh, a plaque commemorating Marjory’s happy life in the Keith family. In Kirkcaldy, two plaques were erected by the Kirkcaldy Civic Society (see also here).

Marjory was buried in the Abbotshall Church graveyard. Next to her grave, a statue dedicated to her was erected in 1930.

I will now give some excerpts from Marjory’s first journal, which includes many short poems. Several of them express her love for her cousin Isabella, for instance the poem “Summer” contains the four verses:

My lover Isa walks with me

And then we sing a prity glee

My lover I am sure shes not

But we are content with our lot

Often the two girls slept in the same bed, but as Isabella complained that Marjory kept fidgeting, she made her sleep head to foot:

ISAS BED

I love in Isas bed to lie

O such a joy & luxury

The botton of the bed I sleep

And with great care I myself keep

Oft I embrace her feet of lillys

But she has goton all the pillies

Her neck I never can embrace

But I do hug her feet in place

But I am sure I am contented

And of my follies am repented

I am sure I’d ratber be

In a smal bed at liberty

Marjory loved animals, nature and the countryside. During most of the summer 1810, she lived with Isabella at Braehead House, near Cramond (in the north-west of Edinburgh), a place which made her happy: “Here at Breahead I enjoy rurel filisity to perfection.” She said later:

Here I pas my life in rurel filicity festivity & pleasure I saunter about the woods & forests

Breahead is far far sweeter than Edinburgh or any other place Everything is beautiful some colour is red others green & white &c &c but the Trees & hedges are the most beautiful for they are of the most pretty green I ever beheld in all my life

I finally give a poem about nature; its four first verses elaborate on four verses from the previous poem “Summer” mentioned above:

I LOVE TO SEE

I love to see the mornings light

That glitters through the trees so bright

Its splended rays indeeds full sweet

And takes away our tast of meat

I love to see the moon shine bright

It is a very nobel sight

Its worth to sit up all the night

But I am going to my tea

And what I’v said is not a lee

In further posts, I will give excerpts from the second and third journals.

Source: Barbara McLean, editor, Marjory’s Book, The Complete Journals, Letters and Poems of a Young Girl, Mercat Press (1999).

Previously published on Agapeta, 2018/04/29.