Does our epoch love children? All children? Official opinion will answer “yes,” but we can look behind this façade. Rather than love for real children, it is rather a worship for an idealised image of childhood innocence. Behind it lurks a pornographic obsession with defilement and sadism. We can see this through the accusations raised by various authors against known men of the past who were known for loving children.

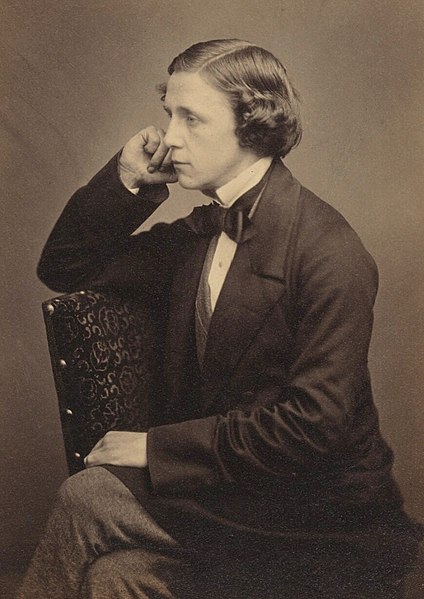

Many famous people have become surrounded by a legend after their death. For example Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, the author of the Alice books better known as Lewis Carroll, has been consistently presented as a shy man shunning adults and living only for little girls; some people, in particular psychoanalists, have proclaimed, with the certainty and smugness typical of expert ignorance, that he was beyond any doubt a paedophile in the clinical sense.

One of the most learned specialists on this illustrious man, Edward Wakeling, the editor of Charles Dodgson’s Diaries, wrote in “The Real Lewis Carroll” (A Talk given to the Lewis Carroll Society, April 2003):

Let me list, in my view, the ten most frequently used myths about Dodgson—in no particular order of merit or level of controversy:

1. He was shy and ill at ease in the company of adults

2. He only liked little girls; he did not like little boys

3. There was a major split with the Liddell family in 1863

4. His relationship with his illustrator, John Tenniel, was strained and terminated after the publication of Through the Looking-Glass

5. He visited Alice Liddell at Llandudno and this inspired him to write Alice

6. He was a mediocre mathematician

7. He was a bad stammerer, but lost his stammer in the company of children

8. He wanted to marry Alice Liddell

9. His relationship with children was unhealthy

10. He gave up photography as a result of scandalous gossip.There are other more spurious and far-fetched accusations such as the following which I will ignore and treat with the contempt they deserve:

11. He was Jack the Ripper

12. He had an affair with Alice’s mother

13. He didn’t write Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland at all—Queen Victoria did!

He then explained at length how most of these myths contradict known facts about his life. Other scholars, in particular Hugues Lebailly and Karoline Leach, published several articles in Contrariwise (the association for new Lewis Carroll studies) showing that, contrarily to the legend, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson appreciated the adult female form, in particular the nude one, that several of his so-called “child-friends” were teenagers or young women (while some—such as Gertrude Chataway—who met him in their tender years, remained “child-friends” for many years after growing up).

In 1996, a quack named Richard Wallace, who claimed both to be a “psychotherapist” and to have spent “25 years in the data processing field,” published a book entitled Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend, in which he claimed that Charles Dodgson and his Oxford colleague Thomas Vere Bayne were responsible for the murders of prostitutes attributed to Jack the Ripper. He based his exposition on making anagrams—bad ones, it seems—of excerpts of two works by Lewis Carroll, The Nursery Alice and Sylvie and Bruno. Several of his linguistic contortions revolve around various sexual practices condemned by religious orthodoxy: masturbation, fellatio, homosexuality, zoophilia, etc. Karoline Leach, in her article “Jack Through the Looking-Glass (or Wallace in Wonderland)“, used every effort to disprove this nonsense, and concluded by categorising it as one of the weirdest manifestations of the “Lewis Carroll myth.”

The writer Guy Jacobson and the puzzle writer Francis Heaney, in the February 1997 letters column of Harper’s Magazine, applied to Wallace his own method, but with much more talent: they made an anagram of one of his paragraphs, in which he confesses having murdered O.J. Simpson’s wife, and also being the author of Shakespeare’s sonnets and a lot of Francis Bacon’s work; one can see it in The Straight Dope, it is quite fun.

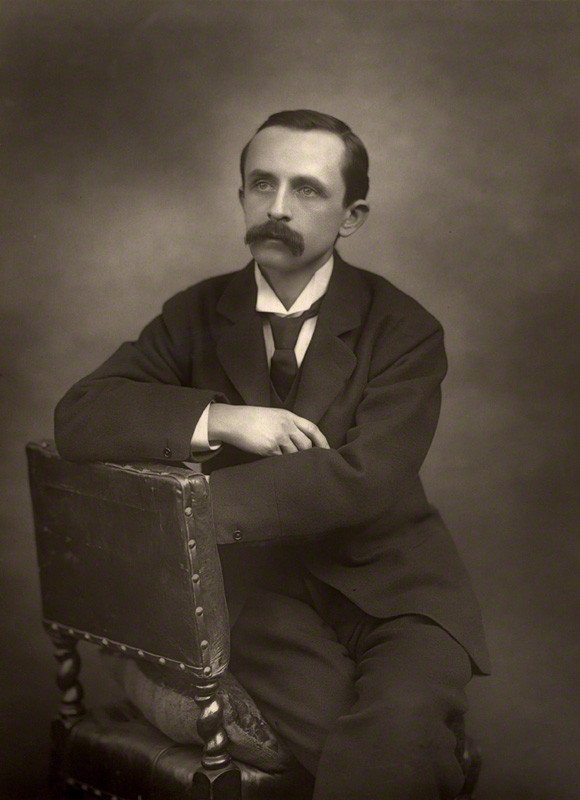

Another writer who suffered similar gossip and libel after his death is James Matthew Barrie, the creator of Peter Pan, the boy who would not grow up. Born in Scotland in 1860, he was the ninth child of ten (two of whom died before he was born). When he was 6 years old, his brother David, his mother’s favourite, died two days before his 14th birthday in an ice-skating accident. His dead brother became in some way the prototype of Peter Pan, as his mother found comfort in the fact that he would remain a boy forever, never to grow up and leave her.

In adulthood, Barrie moved to London and became a successful novelist and playwright. He was married to a pretty young actress named Mary Ansell, but it seems that the marriage was never consummated. He met the five Davies brothers: George (1893–1915), John ‘Jack’ (1894–1959), Peter (1897–1960), Michael (1900–1921) and Nicholas ‘Nico’ (1903–1980). Their father, Arthur Llewelyn Davies (1863–1907), was a barrister, while their mother Sylvia (1866–1910) was the daughter of the famous cartoonist and writer George du Maurier. Sylvia’s brother, the actor Gerald du Maurier became one of Barrie’s favourites, he played the role of Captain Hook.

Barrie became a kind of godfather to the five boys; they inspired him the story of Peter Pan, like the three Liddell sisters (Lorina, Alice and Edith) led Lewis Carroll to imagine Alice in Wonderland.

Arthur died of a sarcoma of the face, and three years later, Sylvia died of a thoracic cancer, leaving the five sons, whom Barrie adopted.

But the tragedy of the family did not end here. When World War I erupted, Jack was already serving in the Royal Navy. George enlisted four days after the declaration of war and was killed in March 1915. Peter likewise volunteered and was invalidated home with shell shock and eczema; when he was demobilised in 1919, he was little more than a ghost. Michael drowned with a close friend at Oxford University in 1921, one month short of his 21st birthday; family members suspected that the two may have entered into a suicide pact. These deaths shattered Barrie.

Peter, a melancholiac plagued by his lifelong identification as “the real Peter Pan” and other personal troubles, committed suicide in 1960 by throwing himself in front of a train. Jack died from lung disease in 1959. Only Nico reached old age.

These successive deaths impressed many imaginative minds. D. H. Lawrence observed in 1921, “Barrie has a fatal touch for those he loves. They die.” Barrie’s biographer Andrew Timothy Birkin, author of J. M. Barrie and the Lost Boys (Constable, 1979; revised edition: Yale University Press, 2003), revealed in the preface to the revised version that his son had been killed in a car crash, one month before his twenty-first birthday, the same age that Michael had drowned. Birkin wrote “I feel somewhat felled by Barrie’s curse.”

The author Piers Dudgeon saw there an opportunity for a successful conspiracy theory presenting Barrie as a psychic serial killer. As wrote Janet Maslin in the New York Times (October 25, 2009), it started with suspicion about the death of Barrie’s brother David:

But it is Mr. Dudgeon who, in sifting through the facts of David’s death, begins thinking that Barrie may have played some role in it and then arranges a meeting in 2007 with a Dutch writer who shares the same suspicion. “I told him rather dramatically that I smelt a rat,” Mr. Dudgeon reveals, rather dramatically. “And immediately he agreed, saying, ‘It is a very smelly rat indeed.’”

Elaborating on this suspicion, he published in 2008 a book entitled Captivated: J. M. Barrie, Daphne Du Maurier and the Dark Side of Neverland. Barely three years later, a new version came out with the title Neverland: J. M. Barrie, the Du Mauriers, and the Dark Side of Peter Pan. One can read in the summaries posted on Internet:

Driven by a need to fill the vacuum left by sexual impotence, Barrie sought out George du Maurier, Daphne du Maurier’s grandfather (author of the famed Trilby), who specialised in hypnosis. Barrie’s fascination and obsession with the Du Maurier family is a shocking study of greed and psychological abuse, as we observe Barrie as he applies these lessons in mind control to captivate George’s daughter Sylvia, his son Gerald, as well as their children—who became the inspiration for the Darling family in Barrie’s immortal Peter Pan.

This fascinating book delves deep, makes links and yields up secrets. It tells how Barrie’s victims—whom he would have not grow up—were lost to breakdown, suicide or early death.

Dudgeon starts from George du Maurier’s bestseller novel Trilby, in which an evil hypnotist named Svengali seduces, dominates and exploits a young girl, and makes her into a famous singer, but destroys her soul. He claims that George was a hypnotist himself and that Barrie learned from him the art of mental manipulation (although there is no record that the two ever met). Then he applied his wicked art to the du Maurier family, Sylvia and her five sons, but also her brother George and his daughter Daphne.

So—according to Dudgeon—as do clever predators, Barrie stalked his victims, conquered the family’s trust and infiltrated it as “Uncle Jim.” Then he could start his work of destruction. Having the parents conveniently dead of disease, he falsified Sylvia’s will in order to assign to himself the guardianship of the five boys. He could thus complete his goal unhindered: to prevent them from growing up. George’s death in the War and Michael’s suicide resulted from his “programming.” Although Barrie died in 1937, Peter’s suicide in 1960 and Jack’s death from lung disease in 1959 were also belated consequences of his “programming.”

He also exerted his evil influence on Gerald and his daughter Daphne. For example, in order to lead them to commit incest, he included in one of his plays a scene where a man and his imagined daughter flirt and sexually tease each other, then he had the man’s role played by Gerald. Daphne’s macabre novels are thus just a revelation of the influence of Barrie’s depravity.

But his murderous trail seems to extend beyond the du Maurier family. As wrote Michael Dirda in the Washington Post (October 29, 2009):

Barrie’s influence—at least in Dudgeon’s view—may even have caused the death of Robert Falcon Scott near the South Pole. The two men became friends after the explorer’s first Antarctic expedition and, according to Dudgeon, Scott was gradually infected with Barrie’s boyish ideas of the heroic. By 1911 Scott had “changed into a man who was self-confident, self-important, petulant, and possessed of a sense of the significance of ‘the explorer’ as the custodian of the British heroic vision, one who needed to suffer and show courage and discipline and duty and endurance, and who would therefore eschew the ‘modern’ technology of exploration because it was, in effect, ‘cheating.’ Scott had become a fantasist, and his expedition was a tragic disaster.” And who inspired this fantastic and fatal self-image? J. M. Barrie.

Such a paranoid nonsense was ridiculed by knowledgeable scholars, in particular Andrew Birkin wrote a letter to the publisher of “Piers Dudgeon’s ridiculous book,” which ended with the following:

Piers Dudgeon is of course entitled to his own opinion, but his book is so full of errors, distortions, half-truths, and his own opinion passed off as fact, that I personally regard it as worthless.

Bob Douglas in Critics At Large (July 10, 2013) gave a scholarly comparison of various biographies of Barrie: Birkin’s, the Hollywood films, and finally Dudgeon’s, of which he clearly has a very low opinion (he ends by quoting Birkin’s above sentence).

A typical fault—and a form of intellectual cowardise—of our epoch is to attribute psychological problems to the bad deeds of outsiders rather than to people themselves or to their family environment. For instance, why should the suicide of Michael and Peter be caused by the “evil influence” of Barrie rather than by what happened in their family? Indeed, as wrote Martin Rubin in the Los Angeles Times (November 7, 2009):

Dudgeon adopts a prosecutorial tone, but there isn’t a jury that would convict on what he serves up. It never seems to occur to him—but it will to the reader—that losing their parents in this hideous manner scarred the Davies boys for life. Surely this, rather than Barrie’s pathetic, exhaustive efforts to compensate for all that loss, was behind the fact that two of the surviving sons later committed suicide. It seems to me just as likely, even from Dudgeon’s own account, that it was the Du Maurier “Svengali” family who ensnared the childish Barrie in its web rather than vice versa. And he ignores evidence that shows it might have been them rather than the playwright benefactor who damaged those children. (After Arthur’s death, with five young sons, Sylvia shared her lonely widow’s bed with her oldest, who was 14!)

But what lies behind these attacks on Barrie? One might simply say that this is the price of celebrity and repeat the words of the writer Clare Boothe Luce (1903–1987): “No good deed goes unpunished.” Nay, there is something else for both Lewis Carroll and James Matthew Barrie: sexual deviance. Dudgeon speaks of “a need to fill the vacuum left by sexual impotence,” and he thinks that the cause rests with his mother who treated him badly. But behind lurks the usual suspicion of paedophilia. Nico, the youngest of the Davies brothers, had clearly denied any impropriety, or even sexuality, on the part of Barrie:

I don’t believe that Uncle Jim ever experienced what one might call ‘a stirring in the undergrowth’ for anyone—man, woman, or child. He was an innocent—which is why he could write Peter Pan.

In a review for the Telegraph (July 13, 2008), the writer Justine Picardie displays—in a quite stereotyped way—current obsessions and fears. She quotes Laura Duguid, Nico’s daughter: “I’m certain that there was nothing paedophiliac about him, but he did write some creepy things in The Little White Bird.” Then Gerald du Maurier’s biographer, James Harding: “One needs a tough stomach to put up with Barrie in this mood. No writer today would publish such an account without inviting accusations of paedophilia or worse.” This novel contains the original story of Peter Pan, but the narrator, a Captain W impersonating Barrie himself, describes also his relation with a boy called David, who looks like George Davies. Now for the “creepy thing,” I quote Justine Picardie:

When The Little White Bird was published in 1902, it was hailed by The Times Literary Supplement as ‘an exquisite piece of work’ and ‘one of the most charming books ever written.’ The same review also declared, ‘If a book exists which contains more knowledge and more love of children, we do not know it.’ But a modern reader might feel less straightforwardly celebratory. Take, for example, the following passage, when the narrator describes his night alone with the child: ‘David and I had a tremendous adventure. It was this—he passed the night with me… I took [his boots] off with all the coolness of an old hand, and then I placed him on my knee, and removed his blouse. This was a delightful experience, but I think I remained wonderfully calm until I came somewhat too suddenly to his little braces, which agitated me profoundly… I cannot proceed in public with the disrobing of David.’

After some time, David climbs into bed with the narrator. ‘For the rest of the night he lay on me and across me, and sometimes his feet were at the bottom of the bed and sometimes on the pillow, but he always retained possession of my finger…’ Meanwhile, the adult lies awake, thinking of ‘this little boy, who in the midst of his play while I undressed him, had suddenly buried his head on my knee’ and of his ‘dripping little form in the bath, and how when I essayed to catch him he had slipped from my arms like a trout.’

Here we see what gives gooseflesh and nausea to the contemporary righteous Briton: a man helps a little boy to undress, feeling a deep emotion in it, finds pleasure in watching his nudity, then shares his bed, holding his hand. Forget about the millions of children in Asia and Africa who die each year of hunger, malaria and lack of sanitation, or the millions of children living in poverty inside affluent contries such as the UK and USA, these things are not creepy, and the media usually don’t care about them. Only the passion of an adult for a child who is not his own provokes disgust.

Carroll and Barrie had no children of their own and they loved other people’s children. This is perceived as undermining the family, and it stirs in many parents jealousy and fear: like the Pied Piper of Hamelin, these men will use magical charms to snatch their children away to Neverland. Questioning their motivations, one suspects a sexual agenda, but finding none, one starts to imagine something worse, a hidden satanic conspiracy.

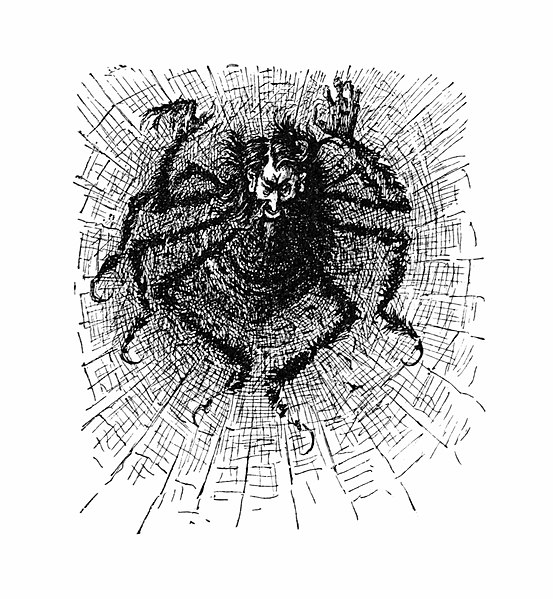

One last thing. In George du Maurier’s novel Trilby, the evil hypnotist Svengali is a Jew from Eastern Europe. George Orwell, in a chronicle entitled “As I Please” in the journal Tribune, wrote on December 6, 1946 a review of Trilby, in which he remarked:

There is no question that the book is antisemitic. Apart from the fact that Svengali’s vanity, treacherousness, selfishness, personal uncleanliness and so forth are constantly connected with the fact that he is a Jew, there are the illustrations. Du Maurier, better known for his drawings in Punch than for his writings, illustrated his own book, and he made Svengali into a sinister caricature of the traditional type.

In the Middle Ages, political rebellion, religious dissidence and sexual deviance, challenging the feudal order, the Church and the institution of the family, were conflated as a single devilish evil menacing the very fabric of society. In particular Jews, as the oldest heretical creed, were reputed—and sometimes still are now—of practicing all possible vices (according to some antisemites, they brought them back from their exile in Babylon). They also suffered the blood libel, the accusation of killing Christian children, either out of hatred of Christendom, or because they needed their blood in order to make unleavened bread for Passover. And today, one often finds conspiracy discourses mixing together Jews, homosexuality, paedophilia, satanism and child murder. It is from this poisoned well that Wallace and Dudgeon—possibly unwittingly—tapped the fetid water that irrigated their libel against two gentlemen who loved children “too much.”

Definitely, our epoch does not love children, and it hates any physical expression of tenderness for them.

This is a revised version of a post previously published on Agapeta, 2015/02/20.