As it describes Ernest Dowson’s look and behaviour, this strange text has been included in the edition by Flower & Maas of Dowson’s letters. The ghost-like appearance of a repulsive man who seems a living dead carrying mould from his own grave, but who also notices every movement of Dowson and Thurston, seems quite surrealistic. But it is also a dire testimony to the poverty and misery that existed in London at the end of the 19th century.

This text relating events at the end of the 1890’s is undated, but it mentions the 1932 film Cynara directed by King Vidor, it was thus written more than 30 years after the incident.

A LONDON PHANTOM

by

R. THURSTON HOPKINS

Towards the end of the eighteen-nineties I was a student at University College in Gower Street, London. That seems to be all that is necessary to say about a fact that is not of the faintest interest to anyone but the writer of this narrative. But what may be of interest to the reader is that it was during this time that there walked into my life (via the Bun House, a haunt of bohemianism in the Strand) that amazing and erratic poet Ernest Dowson. Thin, small-boned, light brown wavy hair which was always curiously upstanding, blue eyes, a tired voice and nerveless, indeterminate hands, with thin fingers, such as are in the habit of letting things fall and slip from them. That is Dowson as I resurrect him from the mists of the dear dead London of the eighteen-nineties. He wore a disreputable out-of-elbows coat that seemed to be distressingly short above his rump. His collar was, I distinctly remember, tied together with a piece of wide black moire ribbon which acted as a poet’s bow and a fastening for his shirt at the same time.

Dowson seldom smiled. His face was lined and grave, and yet it was the round face of a schoolboy and sometimes one might catch a gleam of youth in his blue eyes. At such moments a ghost of a smile would flit over his sombre features and wipe out the fretful expression which generally lurked there.

At that time he carried a small silver-plated revolver in his hip pocket and he seemed ridiculously proud of it. He would produce it, and hand it round for inspection in bars and cafés, without comment, and for no apparent reason at all. I never discovered what risky tortuous paths impinged on Dowson’s life, that he should think it necessary to carry a gun; but perhaps he was toying with the idea of suicide. God knows, he must have found life a very distressing affair, for his thirty years’ existence on earth had been one long catalogue of disillusionments, financial worries and heartbreaks.

I spent many evenings with Dowson in the Bun House. Though the name of this rendezvous has a doughy sound, it never at any time offered buns to its customers. It is just a London tavern, but it was part of the literary and newspaper life of the eighteen-nineties. It was there that I saw Lionel Johnson, the poet, John Evelyn Barlas, poet and anarchist who tried to ‘shoot up’ the House of Commons, Edgar Wallace, just out of a private soldier’s uniform, Arthur Machen in a caped ‘Inverness’ coat which he told me had been his regular friend for twenty years. ‘I hope to wear out four of these magnificent cloaks during my lifetime—anyway I can make four last out a hundred years!’

At that time absinthe was a popular spirituous drink amongst the young poets and literary vagabonds, and I can still see Dowson sitting on a high stool, lecturing on the merits of this opalescent anaesthetic. ‘Whisky and beer for fools; absinthe for poets’; ‘absinthe has the power of the magicians; it can wipe out or renew the past, and annul or foretell the future’ were phrases which recurred in his discourse. ‘Tomorrow one dies’ was a saying which was often on his lips, and he would sometimes add, ‘and nobody will care—it will not stop the traffic passing over London Bridge’.

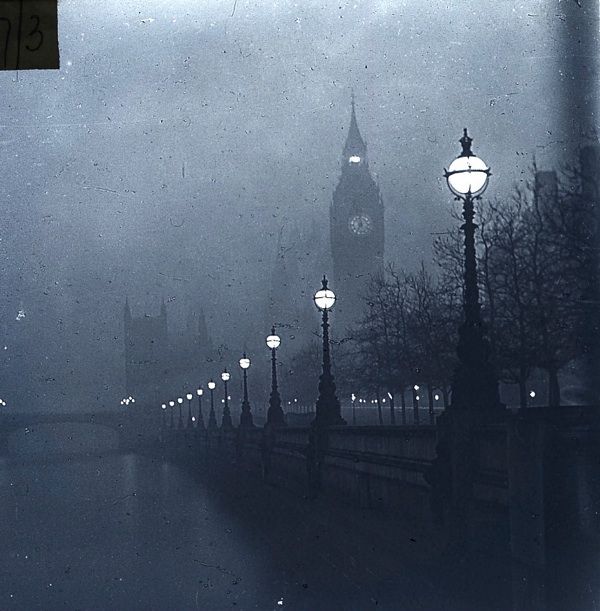

After I had met Dowson a few times at the Bun House we would sometimes rove forlornly about the foggy London streets, initiated bohemians, tasting each other’s enthusiasms. Sharing money and confessions, Dowson wielding a cheap Austrian cigar artfully and blowing smoke rings through his nostrils. As we wandered about London at night we often played a sort of game which we called Blind Chivvy. The idea was to find short cuts or round-about-routes from one busy part of London to another by way of slinking alleys and byways which then were not well known to the average London man.

One evening we were blind chivvying in a puzzle of by-ways, yards, courts and alleys when we became aware of a dark form following us—a figure wrapped up, intent and carrying a gladstone bag. We turned and twisted and he turned and twisted. We could not be mistaken—he was following us. Soon our unwanted ‘companion’ was so close on our heels that we could hear him heavily breathing. At this a foolish feeling of alarm gripped me, but I struggled to save myself from getting panicky.

Nevertheless as soon as we turned into a busy main street I pulled Dowson across to the friendly gas lamps and said to him: ‘Run like the Devil!!’

When we had shaken this unwelcome wayfarer off I asked Dowson if he had caught sight of the man’s face. No he had not; nor had I. But we both had an idea of a dark wrapped-up scarecrow following us through the empty courts with a debauched-looking gladstone bag in his hand.

A few nights later Dowson and I were in a bar parlour having a couple of frugal ‘beers’ when I noticed Dowson patting his pockets to locate his cigarette case. Dowson—who wrote that poem Cynara that has since been popularized all over the world by its use as a title and a motif in one of Ronald Colman’s famous films—was an absent-minded dreamer who never could return his cigarette case to the same pocket twice running. At that moment somebody slipped through the swing door of the bar. He was tall and thin; carried a horrible old gladstone bag; a mummified figure in an overcoat with a crazy old mackintosh over it. His face was almost hidden by a dirty silk scarf which was bound round his jaw as though he had toothache.

Yes! it was the same man who had followed us through the back streets only recently. It is a funny thing to say, but I felt that this figure (or ‘personage’ shall we say?) was not bound by the limits of youth or of age—there was some strange quality about him that was other-worldly. I found it difficult to think of him as a live human being.

Meanwhile Dowson fumbled for his cigarette case with ineffective fingers, without result.

Then a low voice came from the mummy-like figure: ‘Try your hip pocket.’

Dowson dived into the hip pocket and found the elusive cigarette case. We looked up and met the eyes of the visitor. Afterwards we tried to recall why we felt that this man—this personage—was so horrible: why he filled us with the essence of terror and repulsion. I do not remember that we could find any sound reason for thinking that he was so ghastly and abnormal. But certainly we did both agree about one thing. That was that our visitor had a cold kind of face which as Dowson remarked ‘reminded him of a wizened bladder of lard’. It may be guessed that we did not linger over our beer. The idea of speaking to this personage was intolerable to us and so we emptied our glasses and vamoosed.

Yet once again we were to run into this sinister personage. One evening we had walked towards the house in which Dowson lodged (I think it was 111 Euston Road) and when we were about a hundred yards from the iron railings which stood before the basement we saw once again the man with the dissipated gladstone bag. We watched (with frightful perplexity) as the man walked up the front steps of Dowson’s lodgings. That was enough for us. Somehow the idea of sleeping in the same house with this personage was intolerable to Dowson—for we had guessed that our visitor was looking for a bedroom—and so Dowson arranged to sleep at my home at Crouch End for a night or so.

Before we went to sleep that night we spoke, together and to ourselves, asking each other: Why a derelict hawker with a gladstone bag could appear to us so evil and dangerous?

Dowson could not be persuaded to return to the Euston Road caravansary until several days had passed. But when he did enter the house he could not help but observe that his landlady was very agitated about something. She told him that a man who had called and engaged a bedroom for a week had been found dead in his bed the following morning. She said that he had not a penny in his pockets and his gladstone bag, when opened by the police, contained nothing but garden mould or fine soft earth. No one ever came forward to say who the dead man was, so he was buried in a pauper’s grave. He had told Dowson’s landlady that his name was Lazarus. As far as I remember, the police could not trace any of his kinsmen or friends.

I asked Dowson what he made of the affair some time afterwards; and the poet shrugged his shoulders and said in his low and hesitating voice: ‘Let me tell you something, Hopkins. That mould in his bag was graveyard mould … And was it not Lazarus “that had been dead that did come forth from his grave bound in a winding sheet and his face bound about with a napkin”?’

Even after all these years I can still see Dowson’s rather pallid face, and the sombre light in his eyes as he said these words.

There are times when I believe that Dowson and I were inclined to exaggerate the strangeness of a not very unusual set of coincidences, but that I must confess is not my final decision about the case. I am more than convinced that this wretched errant soul was dying on his feet—possibly starving and looking for someone who would take pity on him. But his appearance was so forbidding that no one would heed him. Also I believe that, in truth, he may have possessed some abnormal gift of hanging on to his body some days after death had really claimed it.

Source: The Letters of Ernest Dowson, Desmond Flower and Henry Maas (editors), Fairleigh Dickinson University Press (1967), Appendix D, pages 440–443.

Previously published on Agapeta, 2015/06/16.