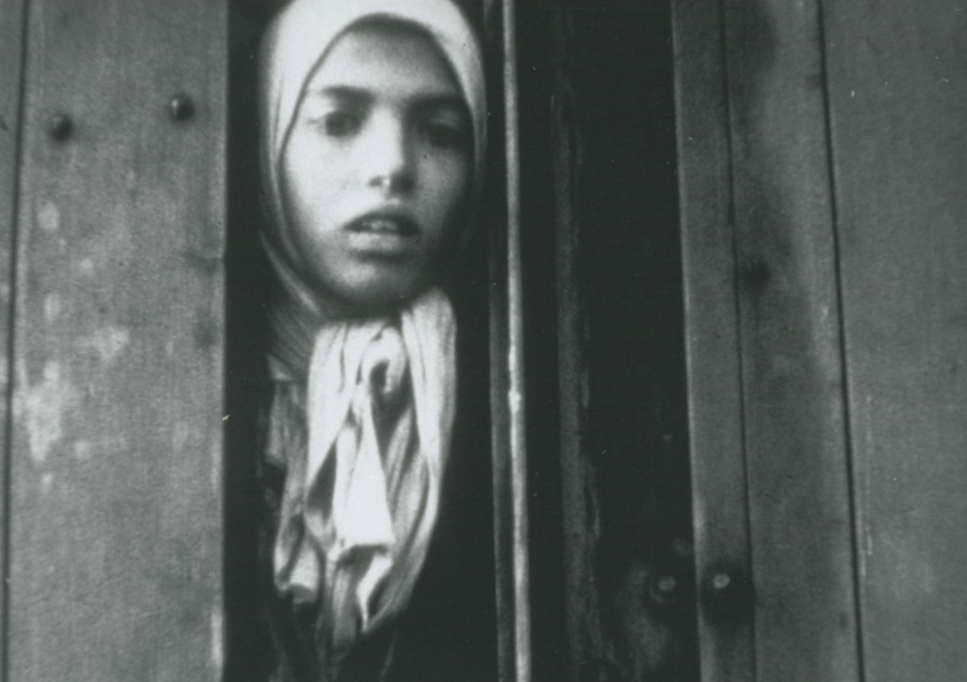

The above picture shows a girl looking terrified as she is locked inside a goods wagon in a train bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. She wears a headscarf made from a torn sheet, because the Nazis shaved her head under the pretext of preventing lice. It was taken from a film shot on May 19, 1944 in the Westerbork transit camp (The Netherlands) by a Jewish prisoner, Rudolf Werner Breslauer, on the orders of the commander of the camp, Albert Konrad Gemmeker.

After the war, this haunting photograph of the anonymous young girl, staring full of fear out of the wagon and about to be transported to death, was used in documentaries and books as a symbol of the Nazi genocide. She was called “the girl with the headscarf” (or “with the headdress”). People simply assumed that the girl was Jewish, since these were the largest group of victims of the Holocaust.

In December 1992, the Dutch journalist Aad Wagenaar started research to identify her. Finally on February 7, 1994, at a trailer camp in Spijkenisse, he met Crasa Wagner, a survivor of Auschwitz, who revealed the girl’s name: Settela Steinbach. Indeed, Crasa Wagner was in the same wagon and heard Settela’s mother call her name and warn her to pull her head out of the opening.

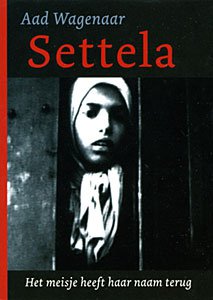

Settela was not a Jew. She was a Roma, she belonged to the Sinti ethno-linguistic subgroup of Roma living in North-West Europe. In 1995 Aad Wagenaar published a book entitled Settela. Het meisje heeft haar naam terug (Settela: the girl has her name back).

Since then Settela Steinbach and her photograph have become a symbol of the genocide of the 220,000 to 1,500,000 Roma / Sinti murdered by the Nazis, to which little attention had been paid. In Roma langage, this genocide is called by some Porajmos (or Porrajmos or Pharrajimos), which means “devouring” or “destruction;” others call it Samudaripen, which means “mass killing.”

The few seconds in Breslauer’s film where Settela appears can be seen on a YouTube film commemorating the Roma resistance in Auschwitz-Birkenau (watch at 1′).

Settela (christened Anna Maria) Steinbach was born on December 23, 1934 in Buchten in the Limburg province of the Netherlands. She grew up in a wagon. Settela and her family were regarded by the authorities as “Dutch gypsies,” however they originally came from Germany.

At that time the Nazis had taken power in Germany, and soon they implemented their policy of racial persecution. Roma were excluded from professional and trade organizations and, under the Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Defects of 14 July 1933, Roma women were sterilized against their will. In 1935 they were stripped of their German citizenship. On December 8, 1938, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler issued his decree calling for the “final resolution of the Gypsy question as required by the nature of race.” On December 16, 1942 Himmler ordered the deportation of all “Gypsy, half-breeds, Rom Gypsies and members of Gypsy tribes of Balkan origin with non-German blood” to a concentration camp. So the Zigeunerfamilienlager Auschwitz (“Gypsy family camp”) was set up in Auschwitz II-Birkenau; contrarily to other camps, here men, women and children were not segregated, families remained united. On February 26, 1943, the first transport of Roma / Sinti men, women and children arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The chief physician at the camp was the infamous SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Josef Mengele, who practiced so-called “medical” experiments on inmates, in particular children. Of the 23,000 Roma imprisoned within the camp during the war, around 20,000 died.

Meanwhile in May 1940, the Nazis had occupied the Netherlands. In July 1943, the German occupying forces instituted a prohibition on the movement of wagons, and all Sinti / Roma were forced into one of 27 guarded assembly camps. Settela’s family ended up at the Eindhoven central assembly camp. On May 14, 1944, police throughout the country received an order by telex: all “gypsy families” were to be transferred to the Westerbork transit camp by Tuesday May 16. Settela’s family and her aunt Theresia were arrested at four o’clock that Tuesday morning during the round up.

On May 19, 1944 the 246 people designated as “gypsies” were forced to board a train going to Auschwitz that also contained Jewish prisoners. The Sinti / Roma, including Settela and her family, were in goods wagons 12 to 17. Just at that moment, film recordings were being made on the orders of camp commander Albert Konrad Gemmeker. Rudolf Breslauer, a Jewish prisoner in Westerbork, who was shooting a movie on his orders, filmed the image of Settela’s fearful glance staring out of the wagon.

Now Himmler had asked to liquidate the Zigeunerlager (Gypsy camp). Young Roma women who had been taken off to dance with German officers (or were forced into prostitution by the SS) learned of the commander’s intention of clearing the whole Zigeunerlager on May 16, by murdering in the gas chambers the 6,000 Roma still in the camp. Then something extraordinary happened: the whole camp population, men, women and children, rose in revolt, they collected stones, wood panels and iron pipes and carved crude knifes from scraps of metal sheets, then barricaded themselves in their barracks. On the 16th, when the Nazis tried to take the Roma from their barracks, they met a fierce resistance, the prisoners managed to repel the first attack that came in the early morning, composed of about 100 German soldiers with rifles and dogs, as they caught them off-guard and in need of orders; then the attackers regrouped and launched a full assault on the Zigeunerlager, which lasted for hours. In the ensuing bloody battle, many Roma were butchered, yet it has been said that the Nazis also suffered several casualties. As the trains that brought new prisoners already arrived during the battle, fears from the authorities that the camp revolt would spread led the Lagerkommandant to call off the attack. The gassing of Roma was thus postponed.

It is in this context that on the 21st (or 22nd), the Dutch Sinti / Roma, among whom Settela and her family, arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the following weeks, one thousand young able-to-work Roma were transferred to Buchenwald, in July another thousand was transferred to other camps, while women were sent to Ravensbrück, leaving but half of the original 6,000 people in the Zigeunerlager, mostly old, weak or sick people, and children; they were starved by reducing their food ration to a minimum. Then on the evening of August 2, the Nazis came, offered the inmates a ration of bread and salami, and told them that they would be transferred to another camp; the SS loaded them on to lorries and drove off in the opposite direction to the gas chambers, then went round and finally brought them there. On the night of August 2/3, 1944, 2,897 men, women and children of Roma or Sinti origin were assassinated in the gas chambers of Birkenau. This “liquidation” of the Zigeunerlager has been called Zigeunernacht (night of the gypsies). It is probably during this night that Settela, her mother, two brothers, two sisters, aunt, two nephews and niece met their death. Of the Steinbach family, only the father survived; he died in 1946 and is buried in the cemetery of Maastricht.

Today, May 16 is remembered as the “Roma Resistance Day.” In Hungary August 2 was designated in 2005 by the Parliament as “Roma and Sinti Genocide Remembrance Day,” yet most European countries make no or insufficient mention of the Roma victims in their official position regarding the Holocaust.

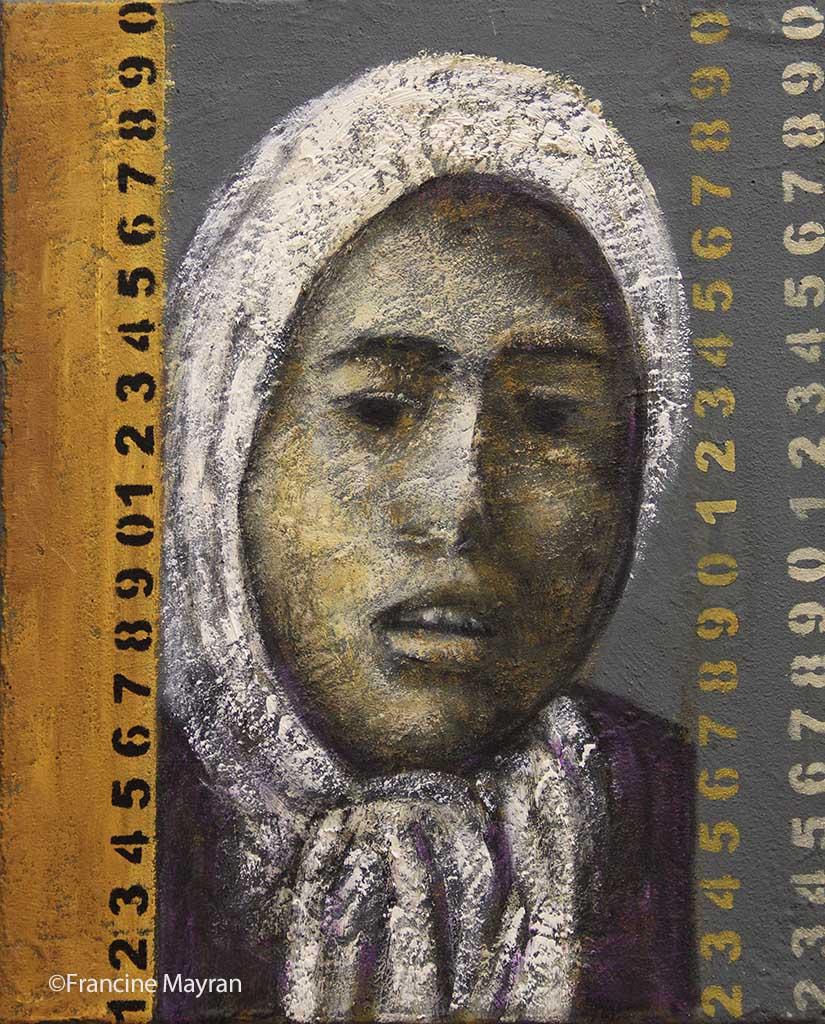

The psychiatrist and painter Francine Mayran has devoted her work to the memory of the main genocides of the 20th century (Armenia, Jews and Romas under Nazism, Rwanda). In particular some of her paintings deal with Roma and children victims of the Nazi Holocaust. From this collection I have selected the above painting of Settela Steinbach. It is an oil on canvas coated with concrete, size 30 × 40 cm.

References:

Settela’s biography:

Wikipedia: Settela Steinbach.

Romedia Foundation, “Settela Steinbach, a nearly-forgotten Sinti-Roma story from WWII,” July 31, 2012.

Rainer Schulze, “Settela’s story,” Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, June 25, 2015.

On the Zigeunerlager, its revolt and liquidation:

Romedia Foundation, “Defiance During the Pharrajimos: Romani Resistance Day,” May 16, 2014.

Romedia Foundation, “Roma Resistance Day: Defiance During the Pharrajimos,” May 26, 2015.

“02/08/1944: Zigeunernacht,” Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.

Donald Kenrick, “Nazi Persecution (Roma and Sinti),” Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.

Rainer Schulze, Auschwitz-Birkenau’s Gypsy Family Camp,” Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, June 8, 2015.

On the Porajmos, its denial or underestimation:

Ian Hancock et al., articles on the Romani holocaust, RADOC, The Romani Archives and Documentation Center.

“Porrajmos: The Romani and the Holocaust with Ian Hancock – Holocaust Living History,” University of California Television (UCTV).

This post merges two posts previously published on Agapeta, 2015/08/02 and 2015/08/13.

Sad story, well written, iconic picture.