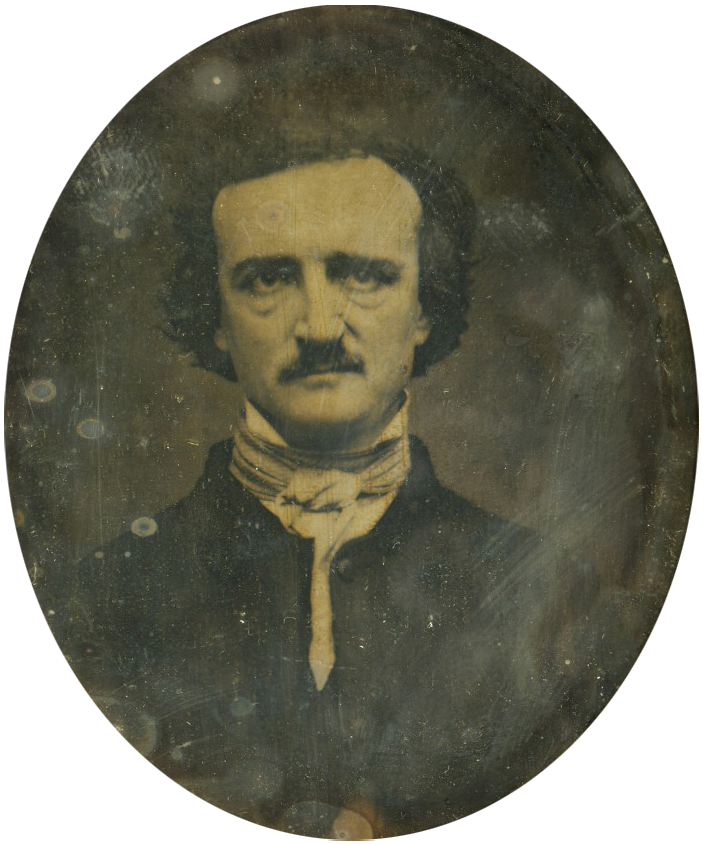

Edgar Allan Poe (January 19th, 1809 — October 7th, 1849) is an American writer known for the strangeness both of his writing and of his life. He was named Edgar Poe, the second child of two traveling stage actors; his father abandoned his family in 1810, and his mother died on December 8th, 1811. His father was also dead then, and Edgar was taken into the home of John and Frances Allan, who served as a foster family, though they never formally adopted him. From them he got his middle name Allan. The family moved to Great Britain in 1815, then back to Richmond, VA, in 1820, so Edgar was educated in both countries.

He had a brief military career, ending in a court-martial for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church; thus he was dismissed in 1831. He then became a professional writer. He is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery. He is considered as a central figure of American romanticism, the inventor of the detective fiction genre and a forerunner of science fiction.

On September 22nd, 1835, Poe secretly married his 13 years old cousin Virginia Eliza Clemm (August 15th, 1822 — January 30th, 1847). On May 16th, 1836, he had a public wedding ceremony with Virginia. Their marriage was blighted by Poe’s love affairs with other women. In January 1842 she contracted tuberculosis, which worsened for five years until she died of the disease at the age of 24. Her illness and eventual death affected him deeply, and he turned to alcohol. Her death also influenced his poetry and prose, where dying young women appear as a frequent motif.

But Poe’s most mysterious story remains that of his own death. On September 27th, 1849, he took a boat from Richmond, VA, and arrived in Baltimore, MD, on the 28th. It seems that he carried a substantial amount of money gathered as a subscription for his proposed literary magazine, The Stylus. Then on October 3rd, he was found delirious on the streets of Baltimore, penniless and wearing shabby clothes that were not his own. He was brought to the Washington University Hospital. Over the next few days, Poe seems to have lapsed in and out of consciousness, but he could never remain coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in this condition. He died in the early morning of the 7th, and it seems that on the night preceding his death, he repeatedly called out a name, “Reynolds” according to some, or “Herring” according to others, but one has found no clear explanation for that name. A biographer gave his last words as “Lord help my poor soul” or, even more improbably, “The arched heavens encompass me, and God has his decree legibly written upon the frontlets of every created human being, and demons incarnate, their goal will be the seething waves of blank despair.” Many hypotheses have been put forward to explain his death, but none is conclusive.

After Poe’s death, the writer, critic and editor Rufus Wilmot Griswold engaged in a posthumous character assassination, creating the legend of the wicked genius; he depicted Poe as a depraved, drunken, drug-addicted madman, known for walking the streets in delirium, muttering to himself; he also claimed Poe was quick to anger, excessively arrogant, and that he assumed all men were villains. This started with the obituary that he published under the pen name “Ludwig” in the New-York Daily Tribune on October 9th. Griswold managed to get recognized as Poe’s literary executor, and he published 4 volumes of The Works of the Late Edgar Allan Poe. The third volume included a biographical article titled “Memoir of the Author,” fabricated by Griswold, including forged letters that he presented as proof of his depiction of Poe.

Griswold’s distortions and lies, in particular those in his obituary, were repeated over and over, even after Griswold’s own death in 1857, producing the long-lived legend of the mad depraved genius. It took several scholarly works, in particular the biographical memoir in John Henry Ingram’s anthology (1874-75) and the critical biography by Arthur Hobson Quinn (1941), to restore a more balanced view of Edgar Allan Poe.

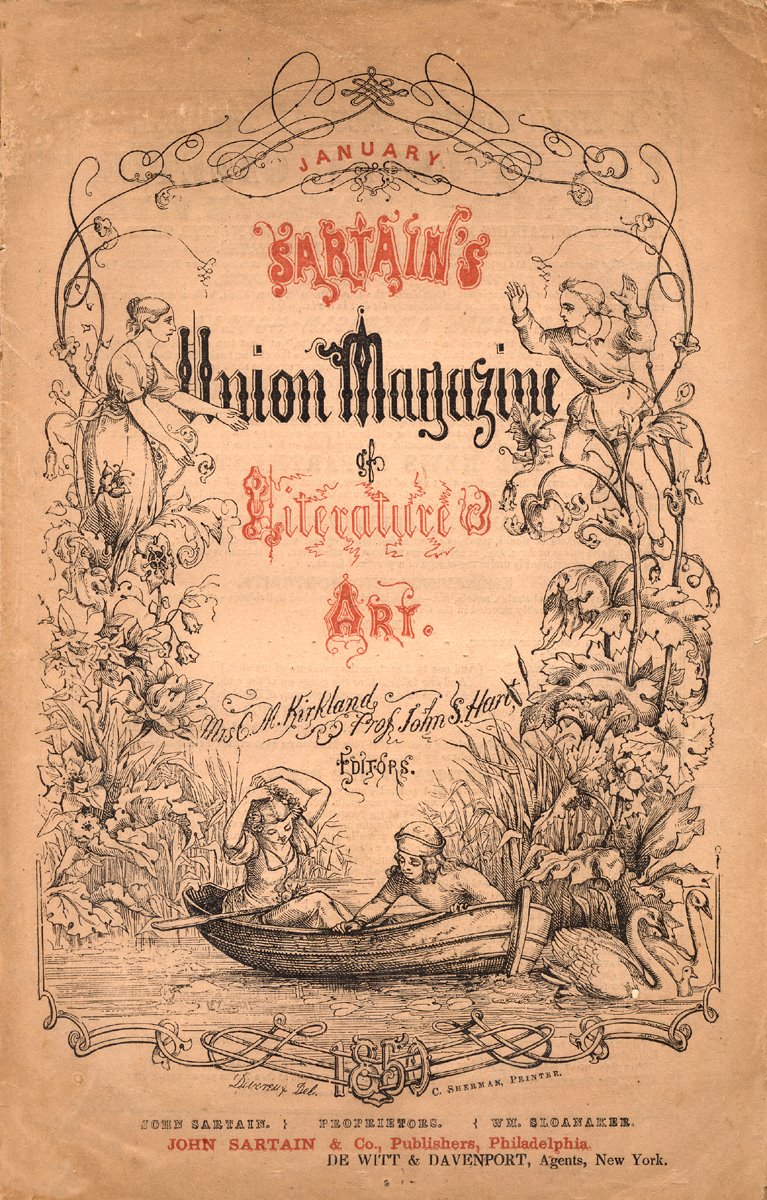

One of his most beautiful poems, about love and death, is Annabel Lee. It is probably the last or second last poem composed by him (in May 1849), and it first appeared on October 9th, 1849, two days after Poe’s death, in the obituary by Griswold. However, the first authorized printing was in the January 1850 issue of Sartain’s Union Magazine of Literature and Art, to which Poe had sold a copy of the poem.

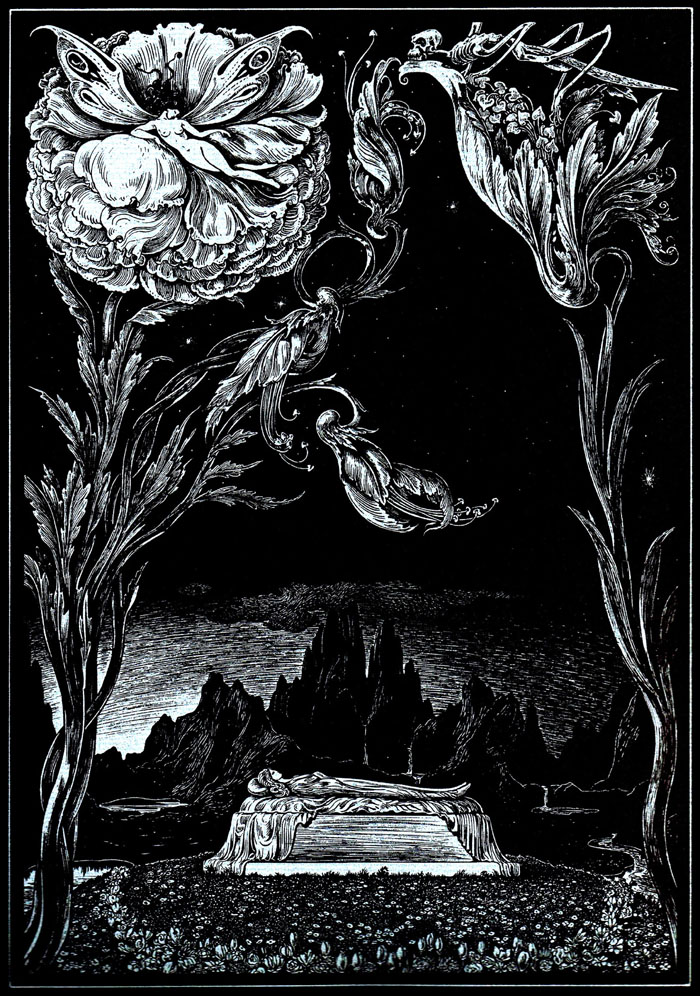

This poem exalts the love between two children as the purest and strongest form that can exist, “a love that was more than love,” “stronger by far than the love of those who were older than we,” a love that survives death. It has been suggested that it was inspired by his wife Virginia’s death, but several other women loved by Poe claimed to be the real inspiration behind the poem.

The version that I give is a transcription of a 1849 manuscript by Poe from the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New York.

Annabel Lee.

By Edgar A. Poe.

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;—

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

She was a child and I was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love—

I and my Annabel Lee—

With a love that the wingéd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud by night

Chilling my Annabel Lee;

So that her high-born kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in Heaven,

Went envying her and me:—

Yes! that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud, chilling

And killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea,

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee:—

For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise but I see the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling, my darling, my life and my bride

In the sepulchre there by the sea—

In her tomb by the side of the sea.

There are many other versions of the poem, a typical one is given in The Works of the Late Edgar Allan Poe, Volume II, Poems and Tales. Beside variations in punctuation, the main differences are the inversion from “She was a child and I was a child” to “I was a child and she was a child” (first line of second stanza) and the change of words from “In her tomb by the side of the sea” to “In her tomb by the sounding sea” (last line).

For a wealth of information on Poe, his life and his works, one can rely on the excellent site of The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Several illustrations of Poe’s works can be seen on Professor H’s Wayback Machine (see in particular here and here for this poem).

Previously published on Agapeta, 2016/05/14.