Everyone knows about Lewis Carroll’s friendship with Alice Pleasance Liddell, who inspired the main character in his famous books Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass; indeed, after a rowing boat travelling during which Carroll regaled Alice and her two sisters with a fantastic story of a girl named Alice who had fallen into a rabbit-hole, she asked him to write it down, and so came Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, the initial version of the first book.

Most people will name Alice when asked about Carroll’s friendships with little girls, and many will not be able to name any other child-friend. It has been said over and over that he was romantically in love with her, and even some have claimed that he wanted to marry her, although there is no evidence for this. Why especially Alice? Apart from the book named after her, she had a sparkling first name and she was a beautiful little girl. Who would not fall in love with such a pretty girl?

But was it a romantic love? And did she love him in return? The arguments for a love affair between Carroll and Alice mention first the poetry he wrote for her, which he included in his books. First, at the beginning of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, we have the poem “All in the golden afternoon” dedicated to the three Liddell sisters, written in a very formal style, showing him as a slave to their demands. Then in Through the Looking-Glass there are two poems dedicated to Alice only, “Child of the pure unclouded brow” (at the beginning of the book) and “A Boat beneath a sunny sky” (at the end of it); both adopt a nostalgic tone, regretting the end of their friendship, and remembering the happy times when he told her stories. The latter poem is an acrostic, the first letter of each line spelling her name Alice Pleasance Liddell, and it contains the verse “Still she haunts me, phantomwise,” which has been interpreted as Carroll being obsessed with Alice. However these three poems look rather like the cold fascination of a worshipper for a remote goddess, there is no warmth in it, no hint of love from her part.

Alice’s mother, full of upper-class prejudice, raised her daughters to marry men in high position, preferably royalty (at one time Prince Leopold courted Alice, but Queen Victoria broke the relation). Hence Mrs. Liddell took care to keep Lewis Carroll away from her daughters as soon as they grew into their teens. And indeed they grew into cold upper-class ladies.

Another argument is Lewis Carroll’s letter to Alice written on March the 1st, 1885, when she was married and nearly 33 years old. It can be found in Chapter 6 of Collingwood’s Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, and also on the blog Phantomwise. In it he says “but my mental picture is as vivid as ever of one who was, through so many years, my ideal child-friend. I have had scores of child-friends since your time, but they have been quite a different thing.” However the object of this letter was to ask her to lend him the original manuscript of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which he had offered her when she was a child, so that he could make a facsimile publication of it. As remarks the above-mentioned blog, the above sentence about her being his ‘ideal child-friend’ was meant as a flattery in order to support his request.

In 1932, at the occasion of the centenary of Carroll’s birth, the 80 years old Alice was invited in the USA, where she gave conferences about the birth of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. One can read one such speech in Chapter 9 of Wakeling’s Lewis Carroll, the Man and his Circle, it is purely formal, devoid of any passion.

What makes me doubt any love affair between Lewis Carroll and Alice is the sharp contrast between this relation and another friendship, loving and warm from both sides, which lasted until his death. This girl is not well-known, in 2016 I checked that her Facebook page had only 4 ‘Likes’ compared to over 1500 for Alice’s. She had an old-fashioned name, Gertrude. And she was not especially pretty, as can be seen from her photographs. In fact I could find only three photos and one drawing of her, and there is not much about her on the web.

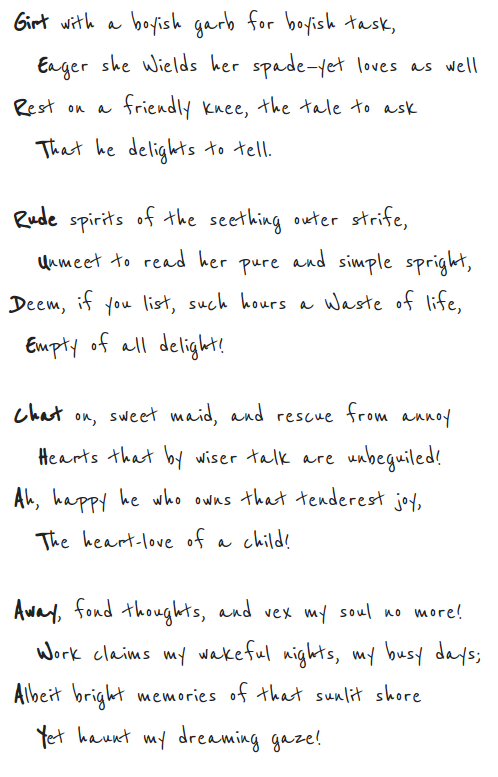

Lewis Carroll’s long nonsense poem The Hunting of the Snark starts with a dedication to a little girl, which mentions her love two times:

Inscribed to a dear Child:

in memory of golden summer hours

and whispers of a summer sea.

Girt with a boyish garb for boyish task,

Eager she wields her spade: yet loves as well

Rest on a friendly knee, intent to ask

The tale he loves to tell.

Rude spirits of the seething outer strife,

Unmeet to read her pure and simple spright,

Deem, if you list, such hours a waste of life

Empty of all delight!

Chat on, sweet Maid, and rescue from annoy

Hearts that by wiser talk are unbeguiled.

Ah, happy he who owns that tenderest joy,

The heart-love of a child!

Away fond thoughts, and vex my soul no more!

Work claims my wakeful nights, my busy days—

Albeit bright memories of that sunlit shore

Yet haunt my dreaming gaze!

It is a double acrostic, both the first letter in each line and the first syllabe in each stanza spell her name: Gertrude Chataway, as higlighted in the manuscript shown below. Double acrostics by Lewis Carroll are rare, this poem seems thus special.

Gertrude Chataway was born in 1866, and she met Lewis Carroll during the summer holiday of 1875. In fact she was enthralled by him and it was her who approached him in the first place. She recalls their first meeting in Chapter 10 of Collingwood’s Life and Letters:

I first met Mr. Lewis Carroll on the sea-shore at Sandown in the Isle of Wight, in the summer of 1875, when I was quite a little child.

We had all been taken there for change of air, and next door there was an old gentleman—to me at any rate he seemed old—who interested me immensely. He would come on to his balcony, which joined ours, sniffing the sea-air with his head thrown back, and would walk right down the steps on to the beach with his chin in air, drinking in the fresh breezes as if he could never have enough. I do not know why this excited such keen curiosity on my part, but I remember well that whenever I heard his footstep I flew out to see him coming, and when one day he spoke to me my joy was complete.

Thus we made friends, and in a very little while I was as familiar with the interior of his lodgings as with our own.

I had the usual child’s love for fairy-tales and marvels, and his power of telling stories naturally fascinated me. We used to sit for hours on the wooden steps which led from our garden on to the beach, whilst he told the most lovely tales that could possibly be imagined, often illustrating the exciting situations with a pencil as he went along.

One thing that made his stories particularly charming to a child was that he often took his cue from her remarks—a question would set him off on quite a new trail of ideas, so that one felt that one had somehow helped to make the story, and it seemed a personal possession. It was the most lovely nonsense conceivable, and I naturally revelled in it. His vivid imagination would fly from one subject to another, and was never tied down in any way by the probabilities of life.

To me it was of course all perfect, but it is astonishing that he never seemed either tired or to want other society. I spoke to him once of this since I have been grown up, and he told me it was the greatest pleasure he could have to converse freely with a child, and feel the depths of her mind.

He used to write to me and I to him after that summer, and the friendship, thus begun, lasted. His letters were one of the greatest joys of my childhood.

On March 13, 1948, she confided her loving memories of Lewis Carroll to the Hampshire Chronicle; the text is reprinted in Chapter 9 of Wakeling’s Lewis Carroll, the Man and his Circle:

Imagine the seaside at Sandown in the Isle of Wight, where lodgings stretched along the front each with its balcony on the upper floor and standing in a little garden with steps leading down on to the shore. Imagine a little girl about 8½ absolutely entranced with the lodger next door. To her he seemed quite an old gentleman. In the morning he came out on to his balcony breathing in the sea air as if he could not get enough; and whenever she heard him coming she would rush out on to the balcony to see him. After a few days he spoke to her: ‘Little girl, why do you come so fast on to your balcony whenever I come out?’ ‘To see you sniff,’ she said. ‘It is lovely to see you sniff like this’ — she threw up her head and drew in the air.

Thus began a long friendship which ended only with his death.

It was the happiest summer holiday of my childhood, that summer of 1875. He was writing The Hunting of the Snark at that time, and was also thinking about Sylvie and Bruno, which he wrote later, and Rhyme? and Reason?. He told me, while we sat on the steps or walked up and down on the shore, many stories in these, as well as others that he thought of at the time. I would dash off into the sea for a little paddle, but even paddling was often forgotten in the delight of the wonderful stories. I took it as a child does, as if it were true, and asked sooner or later for some particulars. That was enough as I now see to start a new train of thought; at once he caught my idea, and off he would go into a fresh series of adventures. He was pleased because my mother let me run in and out of the sea in little bathing pants and a fisherman’s jersey, a thing quite unheard of in those days. He thought it so sensible and told her not to listen to the mothers who were shocked. He and my mother became very good friends, and after that summer he often invited her to bring me to stay with him in Oxford, where he got us lodgings where we could sleep, and we had all our meals with him in his rooms in Christ Church. He also came to stay with us at Rotherwick, not far from Basingstoke, where my father was the Rector.

[…]

There cannot be many of his child friends of so long ago still living. His charm to a child was greatly entranced by the very sympathetic way that he would see the drift of her thoughts and make her feel she was part of the story. He wrote me many letters in the years that followed — lovely nonsense letters. Some are printed in The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll by his nephew, Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, and also in Miss E. M. Hatch’s book.

The drawing below is a sketch by Lewis Carroll made during that holiday, showing her in her strange swimsuit; it has often been reproduced (for instance in Cohen’s biography of Carroll):

Next a photograph of her in the same attire, made the next year (according to Wakeling):

Their friendship lasted, they corresponded and they regularly spent time together during vacation. It seems that contrarily to some other girls, as she grew up she continued to enjoy his way of entertaining her with childish ways. She wrote (see Collingwood):

I don’t think that he ever really understood that we, whom he had known as children, could not always remain such. I stayed with him only a few years ago, at Eastbourne, and felt for the time that I was once more a child. He never appeared to realise that I had grown up, except when I reminded him of the fact, and then he only said, “Never mind: you will always be a child to me, even when your hair is grey.”

Also (see Wakeling):

Many people have said that he liked children only as long as they were really children and did not care about them when they grew up. That was not my experience; we were warm friends always. I think sometimes misunderstandings came from the fact that many girls when grown up do not like to be treated as if they were still 10 years old. Personally I found that habit of his very refreshing. I did not see him often in the last years of his life because I was so much of the time abroad; but the memory of him will always be a very great happiness to me.

Carroll’s letters to Gertrude are full of jokes and puns, and kisses generally play an important role in them. Indeed, his two most famous letters to her (in Collingwood) revolve around kisses. The first one tells how her kisses makes her letters heavier, so that the postman has to charge him an extra:

Christ Church, Oxford,

Dec. 9, 1875.My dear Gertrude,—This really will not do, you know, sending one more kiss every time by post: the parcel gets so heavy it is quite expensive. When the postman brought in the last letter, he looked quite grave. “Two pounds to pay, sir!” he said. “Extra weight, sir!” (I think he cheats a little, by the way. He often makes me pay two pounds, when I think it should be pence). “Oh, if you please, Mr. Postman!” I said, going down gracefully on one knee (I wish you could see me go down on one knee to a postman—it’s a very pretty sight), “do excuse me just this once! It’s only from a little girl!”

“Only from a little girl!” he growled. “What are little girls made of?” “Sugar and spice,” I began to say, “and all that’s ni—” but he interrupted me. “No! I don’t mean that. I mean, what’s the good of little girls, when they send such heavy letters?” “Well, they’re not much good, certainly,” I said, rather sadly.

“Mind you don’t get any more such letters,” he said, “at least, not from that particular little girl. I know her well, and she’s a regular bad one!” That’s not true, is it? I don’t believe he ever saw you, and you’re not a bad one, are you? However, I promised him we would send each other very few more letters—“Only two thousand four hundred and seventy, or so,” I said. “Oh!” he said, “a little number like that doesn’t signify. What I meant is, you mustn’t send many.”

So you see we must keep count now, and when we get to two thousand four hundred and seventy, we mustn’t write any more, unless the postman gives us leave.

I sometimes wish I was back on the shore at Sandown; don’t you?

Your loving friend,

Lewis Carroll.

Why is a pig that has lost its tail like a little girl on the sea-shore?

Because it says, “I should like another tale, please!”

The second one tells how he had to consult a doctor because his face was exhausted from kissing her too many times:

Christ Church, Oxford,

October 28, 1876.My dearest Gertrude,—You will be sorry, and surprised, and puzzled, to hear what a queer illness I have had ever since you went. I sent for the doctor, and said, “Give me some medicine, for I’m tired.” He said, “Nonsense and stuff! You don’t want medicine: go to bed!” I said, “No; it isn’t the sort of tiredness that wants bed. I’m tired in the face.” He looked a little grave, and said, “Oh, it’s your nose that’s tired: a person often talks too much when he thinks he nose a great deal.” I said, “No; it isn’t the nose. Perhaps it’s the hair.” Then he looked rather grave, and said, “Now I understand: you’ve been playing too many hairs on the piano-forte.” “No, indeed I haven’t!” I said, “and it isn’t exactly the hair: it’s more about the nose and chin.” Then he looked a good deal graver, and said, “Have you been walking much on your chin lately?” I said, “No.” “Well!” he said, “it puzzles me very much. Do you think that it’s in the lips?” “Of course!” I said. “That’s exactly what it is!” Then he looked very grave indeed, and said, “I think you must have been giving too many kisses.” “Well,” I said, “I did give one kiss to a baby child, a little friend of mine.” “Think again,” he said; “are you sure it was only one?” I thought again, and said, “Perhaps it was eleven times.” Then the doctor said, “You must not give her any more till your lips are quite rested again.” “But what am I to do?” I said, “because you see, I owe her a hundred and eighty-two more.” Then he looked so grave that the tears ran down his cheeks, and he said, “You may send them to her in a box.” Then I remembered a little box that I once bought at Dover, and thought I would some day give it to some little girl or other. So I have packed them all in it very carefully. Tell me if they come safe, or if any are lost on the way.

Still from Collingwood, a few more funny letters. Here, wishing her a happy birthday, he tells her that he will drink her health until she has none left, and the only remedy will be for her to wait for his birthday and then drink his own health:

Christ Church, Oxford,

October 13, 1875.My dear Gertrude,—I never give birthday presents, but you see I do sometimes write a birthday letter: so, as I’ve just arrived here, I am writing this to wish you many and many a happy return of your birthday tomorrow. I will drink your health, if only I can remember, and if you don’t mind—but perhaps you object? You see, if I were to sit by you at breakfast, and to drink your tea, you wouldn’t like that, would you? You would say “Boo! hoo! Here’s Mr. Dodgson’s drunk all my tea, and I haven’t got any left!” So I am very much afraid, next time Sybil looks for you, she’ll find you sitting by the sad sea-wave, and crying “Boo! hoo! Here’s Mr. Dodgson has drunk my health, and I haven’t got any left!” And how it will puzzle Dr. Maund, when he is sent for to see you! “My dear Madam, I’m very sorry to say your little girl has got no health at all! I never saw such a thing in my life!” “Oh, I can easily explain it!” your mother will say. “You see she would go and make friends with a strange gentleman, and yesterday he drank her health!” “Well, Mrs. Chataway,” he will say, “the only way to cure her is to wait till his next birthday, and then for her to drink his health.”

And then we shall have changed healths. I wonder how you’ll like mine! Oh, Gertrude, I wish you wouldn’t talk such nonsense!…

Your loving friend,

Lewis Carroll.

In this letter he proposes her, as he is too sick to visit her, to be unfaithful in her friendship with him; he compares himself to a bad plum, and advises her to taste the other ones. Note the fractional number of kisses:

The Chestnuts, Guildford,

April 19, 1878.My dear Gertrude,—I’m afraid it’s “no go”—I’ve had such a bad cold all the week that I’ve hardly been out for some days, and I don’t think it would be wise to try the expedition this time, and I leave here on Tuesday. But after all, what does it signify? Perhaps there are ten or twenty gentlemen, all living within a few miles of Rotherwick, and any one of them would do just as well! When a little girl is hoping to take a plum off a dish, and finds that she can’t have that one, because it’s bad or unripe, what does she do? Is she sorry, or disappointed? Not a bit! She just takes another instead, and grins from one little ear to the other as she puts it to her lips! This is a little fable to do you good; the little girl means you—the bad plum means me—the other plum means some other friend—and all that about the little girl putting plums to her lips means—well, it means—but you know you can’t expect every bit of a fable to mean something! And the little girl grinning means that dear little smile of yours, that just reaches from the tip of one ear to the tip of the other!

Your loving friend,

C.L. Dodgson.

I send you 4—¾ kisses.

The following letter shows his longing for her presence, if he can’t meet her on the Sandown beach, she has to come to see him; but then he cannot help making fun at her, that if he comes to Sandown, she will have to give him her bed and sleep on the beach:

Christ Church, Oxford,

July 21, 1876.My dear Gertrude,—Explain to me how I am to enjoy Sandown without you. How can I walk on the beach alone? How can I sit all alone on those wooden steps? So you see, as I shan’t be able to do without you, you will have to come. If Violet comes, I shall tell her to invite you to stay with her, and then I shall come over in the Heather-Bell and fetch you.

If I ever do come over, I see I couldn’t go back the same day, so you will have to engage me a bed somewhere in Swanage; and if you can’t find one, I shall expect you to spend the night on the beach, and give up your room to me. Guests of course must be thought of before children; and I’m sure in these warm nights the beach will be quite good enough for you. If you did feel a little chilly, of course you could go into a bathing-machine, which everybody knows is very comfortable to sleep in—you know they make the floor of soft wood on purpose. I send you seven kisses (to last a week) and remain

Your loving friend,

Lewis Carroll.

Notice here the huge number of kisses:

Reading Station,

April 13, 1878.My dear Gertrude,—As I have to wait here for half an hour, I have been studying Bradshaw (most things, you know, ought to be studied: even a trunk is studded with nails), and the result is that it seems I could come, any day next week, to Winckfield, so as to arrive there about one; and that, by leaving Winckfield again about half-past six, I could reach Guildford again for dinner. The next question is, How far is it from Winckfield to Rotherwick? Now do not deceive me, you wretched child! If it is more than a hundred miles, I can’t come to see you, and there is no use to talk about it. If it is less, the next question is, How much less? These are serious questions, and you must be as serious as a judge in answering them. There mustn’t be a smile in your pen, or a wink in your ink (perhaps you’ll say, “There can’t be a wink in ink: but there may be ink in a wink”—but this is trifling; you mustn’t make jokes like that when I tell you to be serious) while you write to Guildford and answer these two questions. You might as well tell me at the same time whether you are still living at Rotherwick—and whether you are at home—and whether you get my letter—and whether you’re still a child, or a grown-up person—and whether you’re going to the seaside next summer—and anything else (except the alphabet and the multiplication table) that you happen to know. I send you 10,000,000 kisses, and remain

Your loving friend,

C. L. Dodgson.

The following letter was reproduced in her 1948 article in the Hampshire Chronicle, reprinted in Wakeling’s book; Lewis Carroll is cautious about her New Year present of ‘a kiss under the mistletoe’ because it could be that of a boy:

2 January, 1876.

My dearest Gertrude,

I wish you and all your party a very Happy New Year, and many thanks for the card you sent me; as to your other present, I am not quite sure if I am obliged for it or not — you say you wish me ‘a kiss under the mistletoe.’ Now, the question is, who from? It all depends on that, whether I should care to have it or not. Now, my fear is that you mean one of those Sandown boys […] one of those boys who pelted you, you know, when you first went out in your paddling dress. So I think my answer must be ‘thank you, I would rather not.’

It is a bright summer day almost. Is summer beginning with you? When the real warm weather begins again (about April or May let us say) you must beg hard to be brought over to Oxford again. I want to do some better photographs of you; those were not really good ones I did […] it was such a wretched day for it. And mind you don’t grow a bit older, for I shall want to take you in the same dress again; if anything, you had better grow a little younger […] go back to your last birthday but one.

Your ever loving friend,

C. L. Dodgson.

Finally, from Collingwood, this letter written on January the 1st, 1892, when Gertrude was aged 25, with fond reminiscences from their first holiday together:

My dear old Friend,—(The friendship is old, though the child is young.) I wish a very happy New Year, and many of them, to you and yours; but specially to you, because I know you best and love you most. And I pray God to bless you, dear child, in this bright New Year, and many a year to come. […] I write all this from my sofa, where I have been confined a prisoner for six weeks, and as I dreaded the railway journey, my doctor and I agreed that I had better not go to spend Christmas with my sisters at Guildford. So I had my Christmas dinner all alone, in my room here, and (pity me, Gertrude!) it wasn’t a Christmas dinner at all—I suppose the cook thought I should not care for roast beef or plum pudding, so he sent me (he has general orders to send either fish and meat, or meat and pudding) some fried sole and some roast mutton! Never, never have I dined before, on Christmas Day, without plum pudding. Wasn’t it sad? Now I think you must be content; this is a longer letter than most will get. Love to Olive. My clearest memory of her is of a little girl calling out “Good-night” from her room, and of your mother taking me in to see her in her bed, and wish her good-night. I have a yet clearer memory (like a dream of fifty years ago) of a little bare-legged girl in a sailor’s jersey, who used to run up into my lodgings by the sea. But why should I trouble you with foolish reminiscences of mine that cannot interest you?

Yours always lovingly,

C. L. Dodgson.

More letters by Lewis Carroll to Gertrude or to her mother can be found on the blog Phantomwise.

References:

Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll (1898), Project Gutenberg ebook.

Gertrude Chataway, “Memories of Lewis Carroll”, Hampshire Chronicle, March 13th, 1948. Reprinted in Edward Wakeling, Lewis Carroll, the Man and his Circle, I.B. Tauris (2015), Chapter 9.

Source of the images:

Photograph of Gertrude lying on a sofa: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Drawing and photograph of Gertrude in swimsuit: “Para Gertrude Chataway,” Alicenations, August 9, 2010.

Last photograph of Gertrude: Gabriella Angeleti (@gabiangeleti) on Twitter.

Previously published on Agapeta, 2016/12/14.

I have been a LC student scholar since I first saw a photograph of the “real” Alice.

Being a portrait photographer, I was always intrigued and a great admirer of photography and his writings.

I constantly defend him on forums where many label him a pedophile in the modern sense.

I wish those who believe so could read this excellent commentary about his relationships with Gertrude and other child friends.

Maybe it would change the attitude of many who can only see deviance in the innocent relationships he established with children.

His relationships did border on the romantic (in a good way) but that was the the way many artistic men thought of children (the cult of the child) A great book about such relationships including a chapter on Carroll is “Men in Wonderland”.

I also personally believe that Carroll may have had not only nostalgia for childhood, but also gender dysphoria. That would explain greatly, his need to surround himself with mostly young female companions. The death of his mother just when he started college, his role as an older brother to his sisters and the idyllic childhood when compared to the stresses of boy’s boarding school and adult life as a stutterer, may also have shaped his need for child friends. Just my OP.

From the essays by Hugues Lebailly and Karoline Leach in Contrariwise, I guess that LC was probably erotically attracted to young women and teenage girls, in other words, he was an ephebophile. He seems also to have been traumatised by the brutality of “masculine values” at his boarding school.

There is nothing wrong with being a “pedophile in the modern sense.” We love girls as human beings, in addition to any sexual attraction. Sharing friendships with them brings us great joy. Hopefully the world can come to more fully understand us.

I see no contradiction between physical attraction and the tenderness Carroll shows towards his young friends. It’s the kind of tenderness I myself feel.