In the post “Components of Love” I presented the three types of love and friendship according to the ancient Greeks:

- Eros is sexual love, generally driven by beauty; it is discriminating and it can be versatile, blooming or withering fast.

- Storge is natural love, as it exists between members of a family, or the love of parents for children; contrarily to Eros, it is unconditional and long-lasting, and it grows slowly.

- Philia is friendship, generally within a group, mediated by activities shared in common; it includes also philanthropy and humanitarian work.

The ancient Greeks also used the word Agape for affection and tenderness, similar to Storge. Then in Christianity, this word evolved to mean a purely spiritual, selfless and undemanding love embracing all humanity; in fact, such an ideal love is extremely rare in real human beings.

These different forms of love can mix together in various proportions, so they are components of love rather than love-styles. Further clarifications about the subject were given in the post “Confused notions and incoherent terminology about love and sexuality.” Both articles should be read before this one.

Here we will consider forms of Eros, and its possible combinations. Plato’s Symposium presents various theories about erotic love presented by participants to a banquet, and it ends with a magisterial discourse by Socrates, who proposes Eros to be the love of beauty evolving towards the spiritual side: from love for a particular beautiful youth to love of all beautiful youths, then to love of everything beautiful, and finally love of beauty itself.

This leads us to the following questions. What about love that is beauty itself? Rather than poetry being written about love, can love itself become a form of poetry? Can love be a work of art?

Poetry is made in bed like love

Its unmade sheets are the dawn of things

Poetry is made in the woods(La poésie se fait dans un lit comme l’amour / Ses draps défaits sont l’aurore des choses / La poésie se fait dans les bois)

— André Breton, “Sur la route de San Romano” (1948)

We will thus investigate here various aspects of poetry that can be integrated into erotic love.

Compound love

Compared to prose, poetry carries more intense emotions. A way to increase the intensity of love is to combine two or three of the components mentioned above. Indeed, such a love will be stronger; also, compound passions are better balanced and more harmonious than simple ones, thus, as explained by Charles Fourier, they will indeed be more beautiful and more beneficial to society.

The two love components Eros and Storge should mix well. Indeed, they both correspond to interpersonal relationships, contrarily to Philia that occurs rather in larger groups. Now their other features are in contrast: versatile and discriminating Eros versus long-lasting and unconditional Storge. In his book Lovestyles (1976), John Allan Lee describes some love affairs mixing Eros with Storge, and they involve deep emotions; such a love is warm and tender, it embraces not only the lovers, but also their social surrounding. According to him, this combination comes closest to the ideal of Agape.

Let us give two examples of a combination of Storge and Eros.

First, an instance of brother-sister love. As a child, the poet George Gordon Byron had not seen much his half-sister Augusta, as they were not brought up together. They met in adulthood, while Augusta was married to Colonel George Leigh. They entered into a close relationship, and apparently had a real love affair together. It was even rumoured that Augusta’s third daughter, Elizabeth Medora Leigh, had been fathered by Byron himself. The poet named his daughter (his only child born in wedlock) Augusta Ada. Byron also wrote vibrant poems devoted to his half-sister, such as “Epistle to Augusta” and “Stanzas to Augusta,” and in a passionate love letter to her dated May 17th, 1819, he wrote:

But I have never ceased nor can cease to feel for a moment that perfect & boundless attachment which bound & binds me to you—which renders me utterly incapable of real love for any other human being—what could they be to me after you? […] and whenever I love anything it is because it reminds me in some way or other of yourself.

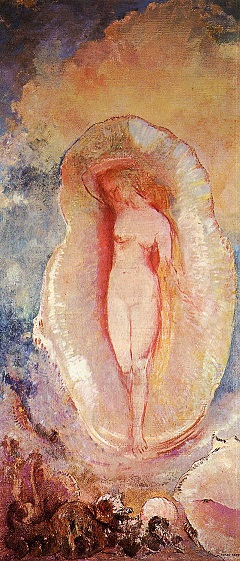

Next, consider mother-child love. Breastfeeding is an intimate and pleasurable contact between the mother and the baby, and some women have experienced an orgasm during it. Dr. Dale Glabach wrote an article titled “Natural Breast-feeding As Lovemaking Between Mother and Her Baby,” where he elaborates an analogy between breastfeeding and sexual intercourse: the breast, whose tip is hardened by touch, penetrates the baby’s mouth and ejects milk into it. Thus he considers breastfeeding as a “nutritive coitus” and a form of love-making.

More astonishing, some women have experienced orgasm during childbirth. The magazine Cosmopolitan spoke with three women who have all had orgasmic births, and there is an organisation called Orgasmic Birth, devoted to educating women about how to enjoy childbirth as an ecstatic experience, rather than the painful ordeal proclaimed by the Bible.

Extremal love

Poetry relies on contrast and on the juxtaposition of seemingly distant objects or ideas, such as in the comparisons “beau comme” of Lautréamont in Les Chants de Maldoror. It also involves unexpected sharp turns. Similarly, the power of love can also be enhanced by joining together opposite extremes.

Many fairy tales base their charm on the love between socially opposite partners, such as a prince and a poor girl. In the 1988 French film Romuald et Juliette, a white man, the CEO of a factory, falls in love with a black cleaning woman who has five children from five different fathers.

Love can also arise between people of opposite ages, as in the film Harold and Maude, about the romance between a death-obsessed young man and a lively 79-year-old woman, who finally commits suicide on her 80th birthday. I have also presented in the post “A Magical Love” the affectionate bond between a 82-year-old man and a 4-year-old little girl. On a symbolic level, Dr. C. George Boeree tells how the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung derived his archetypes of the “wise old man” and the “anima” (feminine side of a man) from his dreams and fantasies:

He carefully recorded his dreams, fantasies, and visions, and drew, painted, and sculpted them as well. He found that his experiences tended to form themselves into persons, beginning with a wise old man and his companion, a little girl. The wise old man evolved, over a number of dreams, into a sort of spiritual guru. The little girl became “anima,” the feminine soul, who served as his main medium of communication with the deeper aspects of his unconscious.

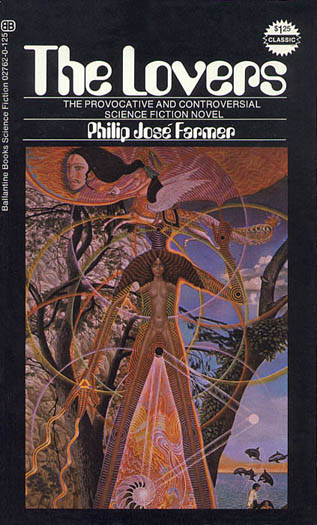

Love can also unite a human being with a partner who apparently is not human, as in the old tale The Beauty and the Beast, where the beast is finally revealed as a charming man who has by witchcraft been transformed into a monster, and who regains his human form through the love of a young woman. Then in some fairy tales, a bewitched prince has been transformed into a frog or a toad, and can only become a man again by the kiss of a girl. But love can also arise between a human being and a truly non-human sentient being. J.-H. Rosny aîné wrote in 1925 his masterpiece novel Les Navigateurs de l’Infini (The Navigators of Infinity). Explorers from Earth land on Mars, where two species are at war; on their return, they bring back two Martians, a father and his daughter; the latter falls in love with one of the human explorers, and thinking strongly about him, she conceives a hybrid child by parthenogenesis. In the celebrated 1961 novel The Lovers by Philip José Farmer, a man escapes the bigotry and puritanism reigning on Earth by joining an expedition to the planet Ozagen, where he has a sexual affair with an insectoid alien taking the appearance of a woman, and he sacrifices everything to that love.

The 2017 film The Shape of Water by Guillermo del Toro, whose story is set in Baltimore in 1962, revolves around the love arising between Elisa Esposito, a mute woman working as a cleaner in a secret government laboratory, and a humanoid amphibian captured from the Amazon River by the US army. This sensitive being is credited by an Indian legend to have magical healing abilities, but it is abused and tortured by the military, who decide to vivisect it, so the woman organises with her friends its escape. Here traditional social values become inverted: the top bad guy is a handsome patriotic officer, while the good people are the amphibian humanoid, Elisa, her black colleague, her homosexual friend, and a scientist who spies for the Soviet Union. In the end, the amphibian and Elisa manage to escape in water, and seem to live happily together afterwards.

Metaphorical love

A metaphor consists in mentioning a thing (object, person, concept, etc.) in order to refer to another one, for instance a budding flower can mean growth from childhood to adulthood. As a figure of speech, it is widely used in poetry. In their book Metaphors We Live By (The University of Chicago Press, London, 2003, see also the transcription by Shumen University), George Lakoff and Mark Johnson showed that metaphor is a fundamental mechanism of mind, that it structures our most basic understandings of our experience and of our interaction with the world. They also explained how the type of metaphor that we associate to some experience can change that experience and the way we act in relation to it.

Some metaphors are toxic (such as the one associating Jews with money and greed), while others improve lives (such as using a rainbow to mean freedom for all sexualities). Let us consider those associated to love. A millennial tradition of sexual repression has led to many negative and toxic metaphors for love, especially for its forms that contradict official social norms. First we have love as dirt, as in “dirty old man” for one courting much younger women, or “pollution” for sexual pleasure without procreation. The word “purity” always means abstinence from sex, never participation in sex. Then love as disease, when a non-standard attraction is considered “unhealthy,” and a person with such an attraction is called “sick;” psychiatry has even labelled some sexual orientations as “mental diseases.” However, contrarily to usual diseases, atypical love does not involve any bacterial, fungal or viral infection, nor does it result from a physical damage to some organs, it does not cause pain, nor does it shorten life; moreover, there is no real cure for it.

A more recent negative metaphor is to label “exploitation” a relation between two people varying widely in age, education or social status. Literally, the word means that one person extracts a monetary profit from the labour of another person. Here, one partner is supposed to be “powerful” and to extract a benefit or gratification from the other “powerless” partner, who offers it and gets nothing in return. One refuses then to consider such a relation as mutual and reciprocal, it must necessarily reduce to a manipulation of the weaker one by the stronger one. The use of this metaphor by people who do not want to see real economic exploitation, and rather accept it as a normal social relation, shows its hypocrisy.

War metaphors have traditionally been used for seduction relations between the two sexes. A man “conquers” a woman, and she “surrenders” to him. Such a view leads men to be overly aggressive towards women, and women to be defensive and to dread men. More recently, a toxic metaphor has linked love with power, so in a relation the partners are supposed to exert their “power” on each other, and any relation between significantly different people is denounced as an “imbalance of power,” as if the two partners were in conflict.

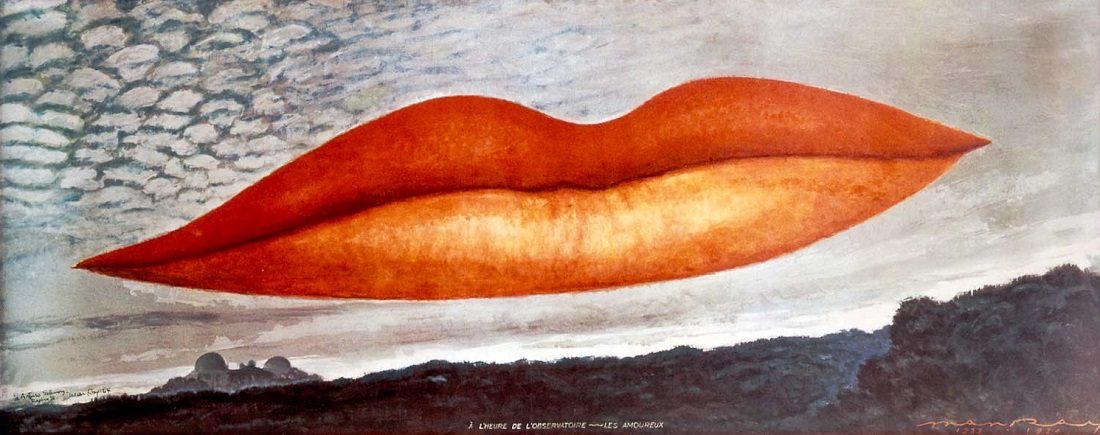

Let us now consider positive metaphors for love. In Chapters 21 and 22 of Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson propose the following beautiful metaphor:

LOVE IS A COLLABORATIVE WORK OF ART

This lead to several meanings. First, the word “collaborative” implies cooperation and reciprocity, so love does not result from a “conquest” and does not lead to “exploitation,” whatever the partners, their age and their status. Next, as a “work of art,” it cannot be “dirty” or “sick,” it is necessarily beautiful, in all its expressions, affective and sexual. Furthermore, the partners will strive to involve art and beauty in all aspects of their relationship. No drab routine, but perpetual creation, surprise and charm.

Metaphors can also be combined. Being beautiful and short-lived, resulting from buds and becoming then fruits, flowers often stand as symbols for young girls in adolescence, no more children and not yet mothers; one says also “young girls in flower” and “flowering girls,” or that a girl is “blooming.” But a young girl is also taken as a symbol of purity, thus flowers can also mean that. Now, being the reproductive organs of plants, flowers can be metaphors for a sexual relation. Indeed, men dating women offer them flowers. Combining these metaphors together leads to associate together sexuality, purity, beauty, flowers and young girls. Beauty purifies sexuality, the love of young girls is beautiful and pure.

A kiss from the universe

The exalted passion of compound love, uniting the extremes, will extend far beyond the lovers, embracing other people, then all nature, finally reaching the sky, the moon and the sun.

Mouth unto mouth! O fairest! Mutely lying,

Fire lambent laid on water,—O! the pain!

Kiss me, O heart, as if we both were dying!

Kiss, as we could not ever kiss again!

Kiss me, between the music of our sighing,

Lightning and rain!Not only as the kiss of tender lovers—

Let mingle also the sun’s kiss to sea,

Also the wind’s kiss to the bird that hovers,

The flower’s kiss to the earth’s deep greenery.

All elemental love closes and covers

Both you and me.All shapes of silence and of sound and seeing,

All lives of Nature molten into this,

The moonlight waking and the shadows fleeing,

Strange sorcery of unimagined bliss,

All breath breathing in ours; mingled all being

Into the kiss.— Aleister Crowley, “Under the Palms,” in Alice: an Adultery, The Collected Works of Aleister Crowley, Volume II (1906)

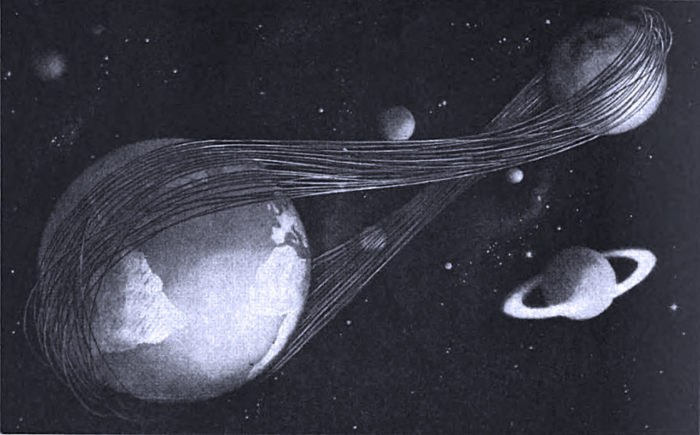

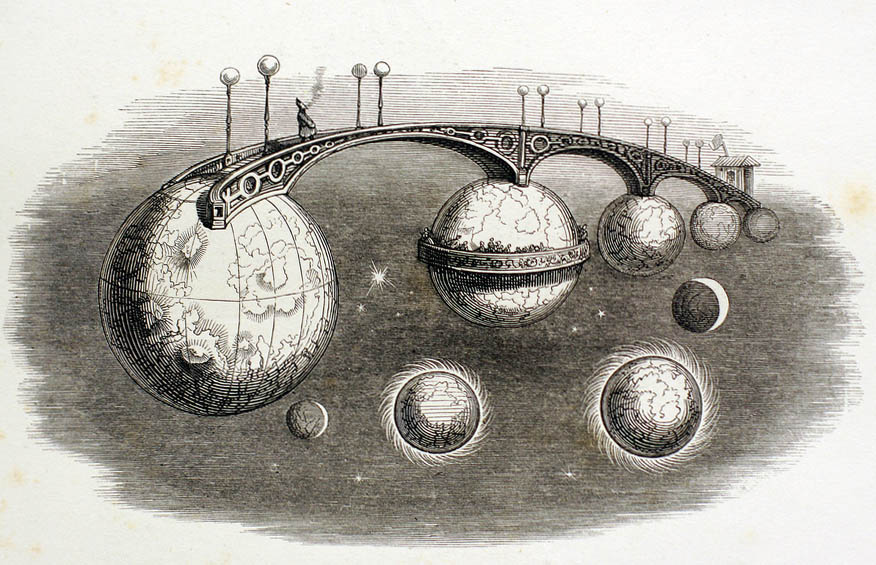

Freed from all fetters, its exalted senses bursting into bliss, the passionate mind travels from planet to moon to planet, all united in a cosmic embrace. Poetic love is a walk through the universe, lovers holding stars in their hands—metaphorically.

Who can be the poets?

Everyone can become a poet and a lover, whatever one’s age, tastes, abilities or education. You can start as soon as you feel ready for it. The poetic republic of love is fully democratic and does not exclude anyone. It accepts all types of love and all types of poetry, they only need to charm the soul by their beauty. I present here some of the most eminent young representatives of this magic country:

Hilda Conkling (1910–1986) started dictating poems to her mother at age 4, and published her first collection of poetry at age 10.

Sabine Sicaud (1913–1928) started scribbling short poems at age 6, and won her first literary prize at age 11. She continued to write verses until her premature death. In the last year of her life, bedridden with disease, she created herself an imaginary lover, Vassili.

Nathalia Crane (1913–1998) started writing poetry on a typewriter at age 9, and published her first collection of poety at age 11. As a little girl, she was in love with Roger Jones, the red-haired janitor’s son.

Minou Drouet (b. 1947) published her first poems at age 8. She was then in love with a 15-year-old boy, Philippe. They pledged to think of each other every day at 8 pm.

Now reader, you can now start experiencing your lovely poetry and your poetic love.

Poetry is a collaborative work of love.

Previously published on Agapeta, 2018/11/18.