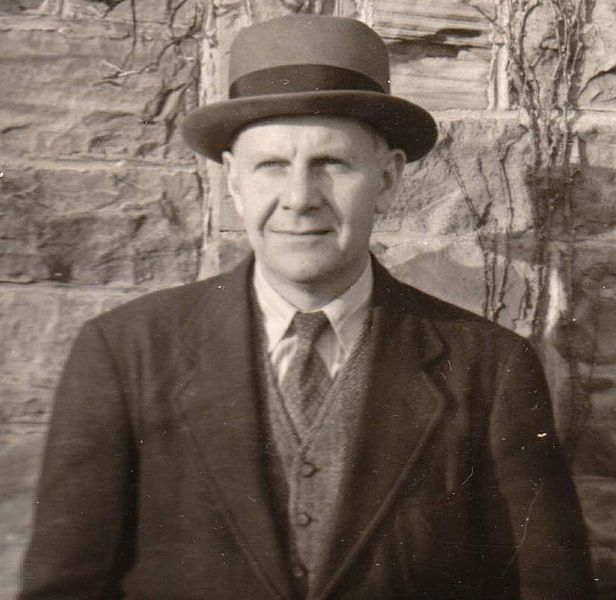

John Crowe Ransom (April 30, 1888 — July 3, 1974) was an American teacher, writer and editor. He is renowned both as a poet and a literary critic. He wrote most of his poems between 1915 and 1927. Together with fifteen other academics and students at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, he founded the group called ‘the Fugitives’ after their magazine The Fugitive (1922–1925). They had a special interest in Modernist poetry, and they published works by Modernist poets, but mainly from the Southern part of the United States of America (the former Confederacy). In 1930, he joined a group of twelve writers who would be called ‘Southern Agrarians’. They denounced industrialism and urbanization, which they saw as an alienating force destroying traditional culture, and they counterposed to it the traditional values of an agarian economy, as it existed in the South before the Civil War. As writes the Poetry Foundation:

As far as Ransom and his fellow Agrarians were concerned, noted John L. Stewart in his study of the poet and critic, “poetry, the arts, ritual, tradition, and the mythic way of looking at nature thrive best in an agrarian culture based on an economy dominated by small subsistence farms. Working directly and closely with nature man finds aesthetic satisfaction and is kept from conceitedness and greed by the many reminders of the limits of his power and understanding. But in an industrial culture he is cut off from nature…His arts and religions wither and he lives miserably in a rectilinear jungle of factories and efficiency apartments.” In short, explained Louis D. Rubin, Jr., in Writers of the Modern South, “for Ransom the agrarian image is of the kind of life in which leisure, grace, civility can exist in harmony with thought and action, making the individual’s life a wholesome, harmonious experience…. His agrarianism is of the old Southern plantation, the gentle, mannered life of leisure and refinement without the need or inclination to pioneer.” Though the rustic dream of the Agrarians more or less evaporated with the coming of the Depression, it left its philosophical imprint on Ransom’s later work. As Richard Gray observed in his book The Literature of Memory, “the thesis that nearly all of [Ransom’s] writing sets out to prove, in one way or another, is that only in a traditional and rural society—the kind of society that is epitomized for Ransom by the antebellum South—can the human being achieve the completeness that comes from exercising the sensibility and the reason with equal ease.”

This reactionary utopia ignored two simple facts: first that the ‘Southern way of life’ of the States that would join the Confederacy rested on slavery and racism, next that it is modern industry, which went together with huge progresses in science and technology, that relieved the majority of humanity from misery, hunger, mass diseases and infant mortality. Anyway, this pipe dream of a mythical South was shattered by the Depression of 1929, which threw into misery millions of working people, including thousands of Southern farmers. By the late 1930s Ransom began to distance himself from the movement, and in a 1945 essay he announced that he no longer believed in either the possibility or the desirability of an Agrarian restoration, which he declared a ‘fantasy’.

At that time, Ransom had turned to literary criticism. His 1941 collection of essays The New Criticism launched a trend that would dominate American literary thought throughout the middle 20th century. This formalist approach emphasized close reading of a work, which had to be viewed as a self-contained and self-referential aesthetic object; thus criticism had to be based on the texts themselves rather than on non-textual elements. As writes the Poetry Foundation:

Using the Kenyon Review (founded by Ransom in 1939) as their principal forum, he and his fellow proponents of the “New Criticism” rejected the romanticists’ commitment to self-expression and perfectability as well as the naturalists’ insistence on fact (mostly scientific fact) and inference from fact as the basis of evaluating a work of art. Instead, the New Critics focused their attention on the work of art as an object in and of itself, independent of outside influences (including the circumstances of its composition, the reality it creates, the author’s intention, and the effect it has on readers). The New Critics also tended to downplay the study of genre, plot, and character in favor of detailed textual examinations of image, symbol, and meaning. As far as they were concerned, the ultimate value (in both a moral and an artistic sense) of a work of art was a function of its own inner qualities.

Ransom won the Bollingen Prize for Poetry in 1951, and his Selected Poems received the National Book Award in 1964.

Three years ago, Ruff Gleeson suggested me the following poem, about the death of a child, probably one of his most famous ones:

Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter

by John Crowe Ransom

There was such speed in her little body,

And such lightness in her footfall,

It is no wonder her brown study

Astonishes us all.

Her wars were bruited in our high window.

We looked among orchard trees and beyond

Where she took arms against her shadow,

Or harried unto the pond

The lazy geese, like a snow cloud

Dripping their snow on the green grass,

Tricking and stopping, sleepy and proud,

Who cried in goose, Alas,

For the tireless heart within the little

Lady with rod that made them rise

From their noon apple-dreams and scuttle

Goose-fashion under the skies!

But now go the bells, and we are ready,

In one house we are sternly stopped

To say we are vexed at her brown study,

Lying so primly propped.

Source of the poem: the Poetry Foundation, copied from Selected Poems, Revised and Enlarged Edition, Alfred A. Knopf, 1969.

Previously published on Agapeta, 2017/01/28.