Today I introduce an English poet of the late 19th century, who loved little girls and wrote beautiful verse for them. I will devote a few more articles to some of his most moving poems.

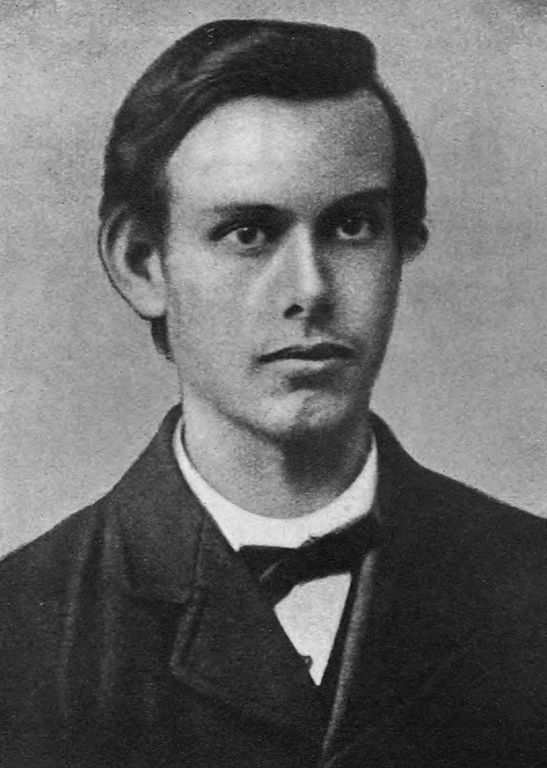

Francis Thompson was born on December 16 or 18, 1859, in Preston, Lancashire, the son of a medical doctor who had converted to Roman Catholicism. At age 11, he was sent to Saint Cuthbert’s College, a Catholic seminary in Ushaw Moor, Durham, in order to prepare him for ordination as a priest. After 7 years, he was dismissed because of his “indolence and absentmindedness.” Then in 1878 he was sent to Owens College, Manchester, in order to study medecine. However he was repelled by the anatomy classes and he could not endure the sight of flowing blood, so instead of attending his courses, he spent his days in public libraries, and he failed thrice in his examinations; however, he never explained his reasons to his father. He finally left Owens College in 1885 and went to London, intending to become a writer. At first his father gave him a small weekly allowance, hoping that Francis would take some job, but his attempts at working failed repeatedly, and this ended in a violent quarrel with his father in November 1885.

Then started his fall into destitution. He lived 3 years on the streets of Charing Cross as a vagrant, surviving by mendicancy, selling matches or newspapers, calling cabs at theatre doors, and sleeping under Covent Garden arches. Moreover, he had become addicted to opium (then called “laudanum”); it has been said that this had started during his second year of medicine, after he read Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas De Quincey.

From time to time he sent to publishers and editors his verse and prose, written for the most part on scraps of paper gathered from the gutter, but he never got a favourable answer. One day he sent to Wilfrid Meynell, editor of the Catholic magazine Merry England, a dirty envelope containing two poems, ‘The Passion of Mary’ and ‘Dream Tryst,’ and a prose essay, ‘Paganism Old and New.’ It was first put aside, but a few weeks later, as Meynell was in want of material for his magazine, he looked at the texts and was deeply impressed by them, so he published them in the numbers for April, May and June 1888. He tried to contact Thompson in order to pay him, but the postal address given by the latter was no longer valid.

Meanwhile Thompson had decided to take his own life. Inspired by the young poet Thomas Chatterton who poisoned himself with arsenic three months before his 18th birthday, he saved all the money he could earn to purchase a lethal dose of opium. After having taken half of it, he had a hallucination, he felt a hand upon his arm and looking up, he saw Chatterton who forbade him to drink the rest. He remembered then that a few days after the young poet’s death, someone had come with the intention of giving him financial support. And indeed, finally Meynell found him, and this changed his life.

Wilfrid Meynell and his wife Alice took care of him. They sent him first to a hospital, then to Our Lady of England Priory in Storrington, West Sussex, where he stayed two years to cure his opium addiction. Afterwards, they lodged him in their own home. He befriended the Meynell children, in particular their four daughters Monica, Madeline, Viola and Olivia. In 1893 he moved to the Capuchin Monastery at Pantasaph, Flintshire.

During these years he wrote his main poetical works, which were published by Meynell, in particular Poems (in 1893), Sister Songs (in 1895) and New Poems (in 1897). Some of his poems express his love for Alice Meynell, and several of them were devoted to the Meynell daughters.

One day he wrote in his notebook “1897: End of Poet. Beginnning of Journalist. The years of transition completed.” Indeed, he did not publish any further volume of poetry after 1897, but he wrote much prose, in particular essays.

The effects of poverty and opium addiction had made serious inroads on his health, and it seems that at the end of his life he returned to his old habit. He died of tuberculosis on November 13, 1907, and was buried three days later in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green.

In Chapter 2 of his Ph.D. Thesis, Joseph J. George analyses the love imagery in Thompson’s poetry. He insists on his love for children, mostly for girls (he explains the absence of boys in his imagery by the bad memories from his education at Ushaw College). Thompson stressed their innocence, compared them to angels. His conception of love for woman was modeled upon the religious love for the virgin Mary, in particular he based love on purity and chastity; to him love was infinitely distant from lust.

The most renowned work by Thompson is his mystical poem The Hound of Heaven (available online as a Project Gutenberg ebook); it apppeared in the volume Poems of 1893, but was probably written a few years before. Following Catholic theology, it counterposes human love to divine love, the latter being all-powerful. In it, there is a strong appeal to a love fusion with children:

I sought no more that after which I strayed

In face of man or maid;

But still within the little children’s eyes

Seems something, something that replies,

They at least are for me, surely for me!

I turned me to them very wistfully;

But just as their young eyes grew sudden fair

With dawning answers there,

Their angel plucked them from me by the hair.

“Come then, ye other children,

Nature’s—share

With me” (said I) “your delicate fellowship;

Let me greet you lip to lip,

Let me twine with you caresses,

Wantoning

With our Lady-Mother’s vagrant tresses,

Banqueting

With her in her wind-walled palace,

Underneath her azured daïs,

Quaffing, as your taintless way is,

From a chalice

Lucent-weeping out of the dayspring.”

So it was done;

I in their delicate fellowship was one—

Drew the bolt of Nature’s secrecies.

I knew all the swift importings

On the wilful face of skies;

I knew how the clouds arise,

Spumèd of the wild sea-snortings;

All that’s born or dies

Rose and drooped with; made them shapers

Of mine own moods, or wailful or divine—

With them joyed and was bereaven.

The poem Sister Songs: An Offering to Two Sisters (available online as a Project Gutenberg ebook), published in 1895, was written four years before, according to the preface by Thompson. It is dedicated “To Monica and Madeline (Sylvia) Meynell” (the two eldest daughters). It consists of four parts: first an introduction called “The Proem,” the word meaning a combination of ‘poem’ and ‘prayer,’ as it lauds the virgin Mary; next “Part the First” made of 9 short poems, then “Part the Second,” a poem in one piece, and finally “Inscription,” a short conclusion. “The Proem” and the 9 poems of “Part the First” have the same song-like structure, a poem followed by a refrain (in italics) dedicated to Sylvia, and each refrain is a variant of the same pattern. Here is the one of Poem 7:

Then suffer, Spring, thy children, that lauds they should upraise

To Sylvia, this Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways;

Their lovely labours lay away,

And trick them out in holiday,

For syllabling to Sylvia;

And that all birds on branches lave their mouths with May,

To bear with me this burthen,

For singing to Sylvia.

A kiss is requested from the girl in Poem 7:

Oh, keep still in thy train

After the years when others therefrom fade,

This tiny, well-belovèd maid!

To whom the gate of my heart’s fortalice,

With all which in it is,

[. . .]

Set open for one kiss.

And also in Poem 8:

A kiss? for a child’s kiss?

Aye, goddess, even for this.

[. . .]

Then, that thy little kiss

Should be to me all this,

In Poem 8 there seems to be an allusion to an event in Thompson’s live: in the depth of his misery and destitution, at the time of his suicide attempt, a prostitute came to his help, she befriended him, gave him lodgings, and shared her income with him; later she disappeared, never to return, probably to avoid tainting his growing reputation. Here she becomes a child, and by kissing the Meynell daughter, he is at the same time kissing both that woman and innocence:

Then there came past

A child; like thee, a spring-flower; but a flower

Fallen from the budded coronal of Spring,

And through the city-streets blown withering.

She passed,—O brave, sad, lovingest, tender thing!—

And of her own scant pittance did she give,

That I might eat and live:

Then fled, a swift and trackless fugitive.

Therefore I kissed in thee

The heart of Childhood, so divine for me;

And her, through what sore ways,

And what unchildish days,

Borne from me now, as then, a trackless fugitive.

Therefore I kissed in thee

Her, child! and innocency,

And spring, and all things that have gone from me,

And that shall never be;

All vanished hopes, and all most hopeless bliss,

Came with thee to my kiss.

“Part the Second” is a long poem, including moral considerations as well as Thompson’s conception of a girl’s sexuality:

Thou whose young sex is yet but in thy soul;—

As hoarded in the vine

Hang the gold skins of undelirious wine,

It ends with:

“Whilom, within a poet’s calyxed heart,

A dewy love we trembled all apart;

Whence it took rise

Beneath your radiant eyes,

Which misted it to music. We must long,

A floating haze of silver subtile song,

Await love-laden

Above each maiden

The appointed hour that o’er the hearts of you—

As vapours into dew

Unweave, whence they were wove,—

Shall turn our loosening musics back to love.”

Some other poems dedicated to the Meynell daughters will be presented in future articles.

References:

- Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, Francis Thompson, Burns & Oates, London (1907), (Internet Archive).

- Joseph J. George, Francis Thompson: the Poet Revealed in his Images, Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Ottawa, 1952.

- Everard Meynell, “Thompson, Francis,” Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement.

- Francis Thompson, The Hound of Heaven, Dodd, Mead & Co. (1926), Project Gutenberg ebook.

- Francis Thompson, Sister Songs: An Offering to Two Sisters, Burns & Oates, London (1908), Project Gutenberg ebook.

This is a revised version of a post previously published on Agapeta, 2016/07/30.

Thank you for this moving account of Thompson’s life.